For a Formatted PDF of this article, click here.

SA’ADYAH AT THE CENTER:

TOWARDS A DIFFERENT NARRATIVE ACCOUNT OF

THE PLACE OF HIS PHILOSOPHY IN THE TRIUMPH OFRABBINIC JUDAISM

Richard Claman

[source]

[source]

THE PROBLEM

Growing up with Leo Schwartz’s Great Ages and Ideas of the Jewish People (1956), I learned that in the period between 330 BCE (with the conquests of Alexander the Great) and 500 CE (‑‑ a traditional date for the end of the period of “Amoraim”, the Sages of the Babylonian Talmud) there existed a “‘Talmudic civilization’”, “a single Jewish cultural pattern that includes the major motifs of life of all of the Jewish communities”, both in the Land and in Babylonia (and elsewhere in the Diaspora), characterized by “the basic homogeneity of social organization and religious orientation throughout the far-flung Jewish settlements in the Rabbinic age.”[1]

From this starting point, a number of consequences, in terms of narrating Jewish history, followed. In particular, as relevant here:

(i) the ‘Geonim’ (‑‑ referring to the heads of the rabbinic academies in Babylonia ‑‑ traditionally dated to 640-1040 CE[2]) were then portrayed as, beginning as of around the 10th century CE, under the influence of contemporaneous Islamic thought, simply translating rabbinic thought into Arabic, and presenting the halakhah in a systematic manner ‑‑ culminating in Maimonides’ code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah;[3]

(ii) the Karaite (or Qaraite) movement (pictured as beginning as early as 750 CE) was then portrayed as a “revolt” against the established and dominant rabbinic ideology of the Oral Torah: “This [anti-rabbinite] feeling was of long standing, but with the momentous change to Arab rule it became articulate”;[4] and

(iii) a Jewish ‘philosophy’ then began to develop, beginning with Sa’adyah[5] Gaon (882-942 CE), and culminating with Maimonides (1138-1204 CE), which borrowed the methodologies of Islamic thought in order to defend Jewish belief against ‑‑ and, when possible, to harmonize Jewish belief with ‑‑ the pure rationalism of the Greek philosophers, whose works had now been translated into Arabic.[6]

Recent scholarship, however, concerning the period now re-labelled as “Late Antiquity” ‑‑ which period, depending on the author, runs from the editing of the Mishnah (around 225 CE) through the Seventh Century (with the conquest of Jerusalem by the Arabs in 638 CE),[7] but alternatively from 500-900 CE (according to Ra’anan Boustan[8]) ‑‑ contends, however, that the process of ‘rabbinization,’ i.e., the process whereby ordinary Jews adopted the specifically-rabbinic concept of halakhah, and accepted rabbinic hegemony (as advocated by the Geonim), was achieved only in around the 10th century.

Thus, for example, David Biale, in his “Introduction to Part Two” of his edited volume, Cultures of the Jews, addressing the period “from roughly the seventh to the eighteen centuries”, explaining:

We might define the “Jewish Middle Ages” as the period when rabbinical Judaism, as expressed in the talmudic literature produced in Palestine and Babylonia, became the dominant practice for the majority of Jews. But this was a process that happened gradually, and the editing of the two Talmud did not coincide with the rabbis becoming the hegemonic authorities.[9]

Such a re-characterization of ‘the Talmudic Age’, and of the period of the Geonim as a continuation thereof, plainly has substantial repercussions for our picture of, e.g., the Geonic period, [10] the ‘revolt’ of the Karaites, and the emergence of Jewish philosophy.

For example, one leading scholar of the relationship between Karaite (or Qaraite) and (what became known as) ‘Rabbanite’ Judaism, has suggested that we need to question the concept of a Karaite ‘revolt’. According to Marina Rustow, who dates the emergence of the Karaites to the 9th-10th centuries, we need to question both (a) the assumption that “non-rabbinic movements represented a rebellion against rabbinic authority rather than a mere failure of rabbinic hegemony”; and (b) the “presum[ption] that the Qaraites had rebelled against a coherent and all powerful rabbinic establishment”.[11] Rather, “the notion that Qaraism branched off from Rabbanism in the ninth century (or the eighth) implies that both began fully formed and remained unchanged in the process. In fact, their histories were so closely intertwined that they shared more than divided them, and defined themselves in contradistinction to one another progressively over the course of several centuries”.[12]

Similarly, Paul Heger has argued that:[13]

Ultimately, the gaonic practice of suppressing and invalidating opposing opinions would constitute one of the factors leading to the creation of the Karaite movement.

(This re-dating of the rabbinization process may also be related to a growing recognition that Islamic law, shari’a, did not simply emerge with Muhammad, but rather emerged over time, reaching a high-point of development only around 900 CE.)[14]

* * *

Since my own field of study is Jewish philosophy, I will focus here more specifically on what the new understanding of the ‘rabbinization’ process might mean for the emergence of Jewish philosophy, as exemplified in Sa’adyah Gaon’s leading work, The Book of Beliefs and Opinions (hereinafter, “BBO”), completed in 933 CE.[15] (Sa’adyah, to be sure, had two predecessors in the prior generation, but (a) little is known of their work, and (b) they did not carry the authority of the geonate.)[16]

In brief, I suggest that we should see BBO as part of Sa’adyah’s across-the-board efforts as a cheerleader for the not-yet-completely-dominant rabbinic Judaism ‑‑ on the one hand, writing polemics against perceived adversaries (including Karaites, and the geonic leadership of the yeshiva in Tiberias), but on the other hand, and more positively, writing a translation into Arabic of the Torah, with commentaries on the Torah and other Biblical books (Isaiah, Job, Daniel, Psalms and Proverbs), writing practical summaries of the governing halakha and responsa on various topics (e.g., evidence, and business partnerships), compiling a definitive ‘siddur’ on the rules (and contents) of Jewish liturgy, and even writing piyyutim (liturgical poems.)[17]

I suggest accordingly that we should read BBO as a formal structure for advocating two very practical ideas in support of the rabbinization program: (i) that God created the world to “benefit” humankind, “so that they might obey him” (Rosenblatt tr., 86), and (ii) that God did so by giving us the commandments, so that we might obey them and “attain[] permanent bliss” (id. 138). (See further infra.)

And this optimistic portrayal of the role of the mitzvot indeed was persuasive for many.[18]

Accordingly, the first part of this article will provide a brief overview of the ‘new’ understanding of the rabbinization process in the Late Antiquity/Geonic periods; and the second part will argue for a new contextualization of Sa’adyah’s philosophy.

[Since we are trying to talk here about ‘ordinary Jews’,[19] one might ask: how many Jews are we talking about, in this period? There is relatively little discussion of this in the literature, because Jewish population statistics are virtually non-existent, and/or are otherwise unreliable, until the modern period. One guess is that the number of Jews living in the Land declined from around 1.5 million persons before the Bar Kochba rebellion, to around 700,000 in the 2rd-3th centuries, to around 200,000 in the 6th century. By contrast, the number of Jews living in Babylonia in these centuries may have stayed steady at around 1.2 million persons.][20]

A.The ‘New’ Picture Of The Ongoing Rabbinization Process

In outline (and disregarding, for this purpose, the nuances and cautions expressed by the different authors), the ‘new’ picture is as follows:[21]

1. in the wake of the destruction of the Second Temple, and the failed revolt of Bar Kochba (135 CE), ordinary Jews in the Land, primarily in the Galilee, continued to pursue programs of Jewish life centered around the synagogue, the Biblical Sabbath and festivals, and symbols drawn from their imaginations/recollections of the Temple. These programs developed over time to include synagogue-based practices of regular readings from the Torah and the Prophets, translation thereof (with some implicit commentary) (in the Targums), and expansion of the synagogue liturgy via poetry, in the form of piyyut which incorporated midrashic-type commentary. The synagogue service may have also included a midrashic sermon/exposition, in a form similar to those preserved in, e.g., Pesikta d’Rabbi Kahana (5th cent.) (“PRK”).[22] The synagogue appears to have been somewhat open to contemporaneous Greco-Roman culture as exemplified by the inclusion in the synagogues of inscriptions dedicated to the persons donating funds for the construction and upkeep of the synagogues. This focus on the synagogue continued to judge from the archeological remains even after the conquest of the Land in 638 CE by the Arabs (although during this last stage there is evidence for an iconic trend).[23] (We have virtually no evidence from Babylonia for this period, outside of the rabbinic literature);

2. by contrast,[24] the ‘Rabbinic Community’ began, following 70 CE, as a small, self-contained movement, in opposition to Rome. The motivating idea seems to have been one drawn from Stoic philosophy: even if I am subject to external oppression, I can still be the ‘captain of my soul,’ by imagining, and living within, an ‘alternative worldview.’ Towards this end, the Rabbinic Community imagined, for example, that the rabbis (or their predecessors) had already been in control of the Temple service prior to the Temple’s destruction. This Community did not, at least initially, feel a need or desire to reach out to include ‘ordinary’ Jews; and indeed, its literature preserves some very harsh and disparaging remarks about ordinary Jews (“am ha-aretz”). Conversely, this Community, in its beginning, did not assert authority over ordinary Jews, nor was it interested in pursuing such authority;

3. At some point, perhaps in the 5th Century[25] (and PRK may provide evidence thereof), there began to be a dialogue between at least some of the previously-insular rabbis, and ordinary Jews. Conversely, the piyyutim of the 6th-7th centuries begin to reflect more ‘rabbinic” teachings.

A key internal development also emerges in the halakhic literature: while the Jerusalem Talmud (edited around 450 CE) tends to advocate a uniformity of halakhic practice (at least within the Rabbinic Community) ‑‑ although it made room for a diversity of ‘custom’ ‑‑ the Babylonian Talmud, especially in its last layer (the “stam”, dating perhaps to the 6th-8th centuries), seems to have advocated a sort of pluralism, with a recognition of a diversity of Jewish practice.

In either event, however, neither the Jerusalem Talmud, nor the Babylonian Talmud, is a code of practice. But at some point,[26] the Geonim seek to transform the Talmud into a code of practice ‑‑ to correspond to the emerging Islamic shari’a. Thus, Michael Chernick summarized[27]:

The gaonate, the central legislative and academic institution of Babylonian Jewry, consciously used the Talmud in constitutional fashion. Among its activities were establishment of the rules for deciding the disputes that covered the Talmud’s pages and production of legal codes based on the Talmud. At a more advanced stage, the gaonate used the Talmud to respond to questions that were sent to it from the Jewish communities it controlled, thereby creating a genre called responsa. Responsa are still produced today by outstanding Jewish legal authorities, whose advice is sought by those seeking a reply to a contemporary legal, ethical, or religious question. The gaonic use of the Talmud was clearly pragmatic. Having received right to autonomy under the Islamic caliphs in Baghdad, the Jewish community had to find a means of self-governance. The Talmud provided the source for the community’s legal system. Modeling itself on the caliphate’s vision of an Islamic empire united by a uniform Islamic way of life, the gaonate sought to be the single authority for Jewry through its efforts at standardization of Jewish practice. We need to recognize that the gaonic agenda conflicted directly with the Talmud’s open-endedness and pluralism, but it was culturally and politically appropriate to its time. While it abandoned the Talmud’s implicit ethos, it used the Talmud’s explicit dicta to preserve and advance Jewish life. The gaonate’s model became paradigmatic for Oriental Jewish culture, whose most famous postgaonic rabbinic figures, Isaac Alfasi and Moses Maimonides, are best known for their codes and responsa.

Moreover ‑‑ and perhaps as a counter-argument to the pluralism exemplified by the four schools of shari’a then developing within Islam (see fn. 14, supra) ‑‑ the Geonim in Babylonia insisted that halakha must be uniform, both in Babylonia and in the Land, so that practice in the Land needed to change to conform to practice in Babylonia.[28]

This new insistence on uniformity was resisted by some ‘ordinary’ Jews, and that opposition coalesced over time under the label ‘Karaites.’ The task facing Sa’adyah Gaon, accordingly, was both (i) to polemicize against those opposed to Babylonian uniformity ‑‑ and even against the Gaon of the yeshiva in Tiberias, as necessary, but also (ii) to present a positive advocacy of this halakhic ideology that could be accepted by ordinary Jews.

And Sa’adyah seems to have been successful, in hindsight, in his advocacy program.[29] Thus, for example, S.D. Goitein reports, based on his studies of the Cairo Genizah materials, that by the 11th Century, the ideological picture within Judaism had been clarified, and the battles had ended: everyone was now a Rabbanite ‑‑ except for the Karaites.[30] Moreover, there had been a shift in the Jewish population, with a decline in both Babylonia and the Land, in favor of new diaspora communities in North Africa and Spain ‑‑ who accepted the Geonic uniformity approach, even if they rejected details of Geonic teaching.[31]

B. Sa’adyah As Philosopher

(i) Approaching BBO

Sa’adyah, in BBO, presents what appears to be a systematic philosophic statement ‑‑ following, indeed, the structure of systematic Islamic (‘kalam’) thought.[32]

Sa’adyah thus begins with epistemology ‑‑ how can we know anything? And he argues that there are four sources of true knowledge: sensation, intuition, logical inference, and traditions vouchsafed to Israel.

Given that epistemology, Sa’adyah then tries to prove that this world was created ex nihilo, by a single omnipresent and omnipotent God.

Sa’adyah then explains that because this God is also good, in his goodness He (a) created humankind, and (b) gave us the mitzvot, whereby we can achieve eternal reward. (In this context, Sa’adyah also shows that these mitzvot, having been conceived-of from the start of creation for this purpose, are not subject to replacement, or abrogation, by other religions.)

Sa’adyah then proceeds to discuss, among other things, (a) how humans can have free will if God is omniscient, (b) the function of repentance, (c) the nature of the soul, (d) resurrection and the world to come; and (e) the proper course for living.

This systematic form of presentation, however, is, I suggest, just that ‑‑ a form. But we should not mistake the form for the central insight. Consider, for example, Immanuel Kant. It has been cogently argued that his famous epistemology was in effect reverse-engineered to ‘derive’ his desired outcome.[33] Kant accepted Newtonian science. But he also wanted to maintain a basis for believing in God. And so, over time, and in different versions over time, he articulated a two-part structure where (a) knowledge of the physical world can be obtained by applying conceptual frameworks to experience; but (b) there exists a separate type of knowledge e.g., of God, and of the Soul, and of the possibility of freedom hat can be known only through ‘moral’ understanding. And Kant himself admitted that it was the desired end-point that drove him to modify, over time, his ‘foundations’ analysis.[34]

We should heed here, I suggest, the cautionary statement of Robert Nozick, expressing a reality known all too well to those of us who try write ‘constructive’ philosophy. We begin with an insight. We try then to formalize it, with premises and consequences. But life and philosophy are inherently complex. As we write, we become aware of the weak points in our attempt to formalize. And so we “push[] and shov[e] things to fit into some fixed perimeter of specified shape,” and when everything seems to ‘fit’ for a moment, we “quickly … find an angle from which it looks like an exact fit, and take a snapshot, at a fast shutter speed before something else bulges out too noticeably.”[35]

Indeed, as Rebecca Newberger Goldstein has explained, even the seemingly most systematic of philosophers Spinoza, in his Ethics omitted to mention his central underlying assumption/conviction viz., that all facts must have explanations.[36]

Finally, we note how Maimonides generally rejected the ‘philosophic’ framework of BBO, asserting that it constituted in effect just cherry-picking amongst available arguments, without an attempt at internal self-consistency. (Guide of the Perplexed, Book I, chs. 75-76). Whether Maimonides’ criticism was fair or not, it misses, I suggest, the key point ‑‑ that we need to ‘bracket’ the framework, and instead to focus on identifying the central insight that Sa’adyah, for better or for worse, is advocating.

Likewise, I propose to leave-aside the debate as to whether Sa’adyah’s various framework arguments for, e.g., creation, or God’s nature, were all just borrowed from Islamic philosophy, or whether his arguments in these regards had innovated in any way.[37] My suggestion here is that we need to focus on Sa’adyah’s central insight, and its purpose ‑‑ in its historical context, as an argument for rabbinization.

(ii)Sa’adyah’s Central Insights/Contentions

Sa’adyah’s central contentions, I suggest, are as follows:

1. God created humankind in His kindness, as the purpose of creation, and for our benefits ‑‑ by reason of our capacity to obey the mitzvot, and earn reward therefor (at 83, 181-183);

2. imposing mitzvot, so that we can achieve reward therefor, is indeed the best way for God to have expressed His kindness towards us (at 137-138), and

3. the mizvot given to Israel are indeed eternal (at 158).

Thus, Sa’adyah wrote, as an introductory “Exordium” to his “Treatise III: Concerning Command and Prohibition” (at 137-138, brackets by Rosenblatt, tr.):

It behooves me to preface this treatise with the remark that once it is realized that the Creator, exalted and magnified be He, is eternal, nothing having been [associated] with Him [originally], it must be recognized that His creation of all things was purely an act of bounty and grace on His part. Also, as we noted at the end of the first treatise of this book, in regard to the motive of the Creator in creating the world, and in accordance with what is found written in the Scriptures, God is bountiful and a dispenser of favors. Thus Scripture says: The Lord is good to all; and His tender mercies are over all His works (Ps. 145: 9).

Now His first act of kindness toward His creatures consisted in His giving them being—I mean His calling them into existence after a state of nonbeing. Thus did He also express Himself toward the elite of His creatures, saying: Every one that is called by My name, and whom I have created for My glory … (Isa. 43: 7). In addition to that, however, He also endowed them with the means whereby they might attain complete happiness and perfect bliss, as Scripture says: Thou makest me to know the path of life; in Thy presence is fulness of joy, in Thy right hand bliss forevermore (Ps. 16:11). This means the commandments and the prohibitions prescribed for them by God.

Now this remark is the first thing that strikes the attention of the reflecting mind, prompting it to ask: “Could not God have bestowed upon His creatures complete bliss and permanent happiness without giving them commandments and prohibitions? Nay it would seem that His kindness would in that case have contributed even more to their well-being, because they would be relieved of all exertion for the attainment of their bliss.”

Let me, then, say in explanation of this matter that, on the contrary, God’s making His creatures’ diligent compliance with His commandments the means of attaining permanent bliss is the better course. For according to the judgment of reason the person who achieves some good by means of the effort that he has expended for its attainment obtains double the advantage gained by him who achieves this good without any effort but merely as a result of the kindness shown him by God. In fact, reason recognizes no equality between these two. This being the case, then, the Creator preferred to assign to us the ampler portion in order that our reward might yield us a double benefit, not merely a compensation exactly equivalent to the effort, as Scripture also says: Behold, the Lord God will come as a Mighty One, and His arm will rule for Him; behold, His reward is with Him, and His recompense before Him (Isa. 40:10).[38]

This might be characterized as an optimistic presentation of Judaism.[39] Compare, for example, Sa’adyah’s statement (at 66) that “the All-Wise did not create evil. He merely creates those things that are capable of becoming, though man’s choice, sources of peace or evil”.

I suggest that his position concerning the role of mitzvot then ‘drives’, for example, Sa’adyah’s ‘revelation-only’ view of the Oral Torah, even as he drew upon contemporaneous Islamic concepts in support thereof.[40] In short, if the revealed mitzvot are what warrant the double-reward, then that category, for Sa’adyah, will need to incorporate the entire Oral Torah.

Likewise, I suggest that Sa’adyah’s need to present a tangible reward for performance of the mitzvot drives his insistence on physical resurrection ‑‑ a point on which the rabbinic literature was vague.[41]

(By contrast, for Maimonides, in his Guide for the Perplexed [published in 1190], God is essentially indifferent to humankind.[42] That is not, however, I suggest, a position likely to appeal to the ordinary practicing Jew; but Maimonides was not writing to persuade ordinary Jews ‑‑ leaving aside Karaites ‑‑ to become rabbinic Jews: by his day, the rabbinization process had been completed.)

I am not suggesting that Sa’adyah’s positions, as just summarized, are novel: indeed, his emphasis on reward in the world-to-come would have been familiar from contemporaneous Islamic thought.[43]

Sa’adyah’s positions ‑‑ presented as univocally correct ‑‑ do, however, I suggest, stand in contrast to the articulation of various alternative positions in the prior rabbinic literature.

Thus, to take one example[44]: One familiar rabbinic position concerning the question why we should observe the mitzvot was expressed in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) (perhaps 3rd cent. CE, but incorporated into the Mishnah) by one of the very early teachers, Antigonus of Sokho (ch. 1, vs. 3) as follows:[45]

Antigonus of Sokho received from Simeon the Righteous. He would say: Do not be like slaves [‘abadim] who serve the master for the sake of receiving a food allowance [‘al menat leqabbel peras]. Rather, be like slaves who serve the master not for the sake of receiving a food allowance, and let the fear of Heaven [mora’ shamayim] be upon you.[46]

We might categorize this view as falling within those rabbinic approaches that prioritize the ‘acceptance of the yoke of Heaven’ ‑‑ with observance of the commandments then following from that fundamental acceptance.[47]

By contrast, there was ‑‑ as Abraham Joshua Heschel stressed ‑‑ an element of rabbinic thought that emphasized how our observance of mitzvot somehow was necessary to, and did, strengthen God’s presence in this world, quoting how Rabbi Simeon, a disciple of Rabbi Akiva, understood a verse from Isaiah (43:10) as teaching “When you are my witnesses, I am God, but if you are not My witnesses, then, as it were, I am not God”.[48]

Heschel also notes that “The view that says ‘the mitzvot were given for the sole purpose of purifying human beings’ does not comport with the view that declares that the Holy and Blessed One puts on Teffilin and observes the mitzvot”. [49]

But there also indeed existed a rabbinic teaching that “God desired to confer merit upon Israel. He therefore gave them a voluminous Torah and a great many mitzvot.”[50]

Our point is that, as a good salesperson, or cheerleader, we should see Sa’adyah as having focused upon a central concept that, in his view, would be most persuasive, in terms of convincing contemporaneous ‘ordinary’ Jews to accept the rabbinic program – in its daily practice, and in its theological orientation ‑‑ of a uniform halakhah as determined by the Babylonian Geonim.

And it appears that Sa’adyah’s program was indeed generally accepted by, e.g., the emerging Jewish communities of France/Germany (“Ashkenaz”), and in particular by the school known as ‘Hasidei Ashkenaz’, flowering in the early 1200’s.[51] (Indeed, it appears that our picture of ‘rabbinization’ is a retrojection of our idealized conception of the Jewish communities of early Ashkenaz.)[52]

CONTINUING CONSEQUENCES

If the foregoing ‘revised picture’ is correct, then ‘we’ became ‘rabbinic Jews’ not because of the persuasiveness of the rabbinic world view(s) as expressed in the rabbinic literature itself (‑‑ recognizing the pluralism of such worldviews in that literature), but rather because of how Geonic thought, led by Sa’adyah, in BBO, extracted from the rabbinic literature a single particular world-view, and promoted that single picture.

Perhaps Sa’adyah’s picture of eternal reward was compelling at that time ‑‑ particularly within an Islamic civilization with a strong belief in eternal reward, and later within a medieval Western Christendom that also endorsed such a belief.

But perhaps we can today continue the ‘tradition’ even if we reject Sa’adyah’s picture, in favor of alternative pictures ‑‑ whether already expressed within the rabbinic literature itself, or developed in our own age ‑‑ as to, e.g., the role of halakha in achieving meaningful Jewish lives.[53]

Even if a certain uniformity came to characterize the halakhic world-view at the time of (and/or in the wake of) Sa’adyah, I would suggest that, by identifying the historical context in which that development occurred ‑‑ and how it was tied to medieval conceptions of creation and the world-to-come that are difficult for some of us to accept today ‑‑ we might also be able to perceive additional alternatives within the overall tradition.

And as for Jewish philosophy: I suggest that it played a key role in the battle fought in the 10th Century; and perhaps it can play a key role today.

-

Gerson D. Cohen, “The Talmudic Age”, ch. 7 in Leo W. Schwartz, ed., Great Ages and Ideas of the Jewish People (NY: Random House; 1956); quotations from pp. 145 and 147-148. ↑

-

See, e.g., Marina Rustow, Heresy And The Politics of Community: The Jews of the Fatimid Caliphate (Ithaca: Cornell U.P., 2003) at 4-5 ‑‑ challenging this traditional picture, and noting that we have little evidence concerning the Babylonian Geonim until the latter part of this period. Rustow also shows how the material from the Cairo Genizah demonstrates that a geonate continued to function in the Land of Israel until the First Crusade (in around 1096). ↑

-

Abraham Halkin, “The Judeo-Islamic Age”, ch. 9 in Schwartz, Great Ages, supra, see esp. at pp. 223-226. ↑

-

Halkin, “Revolt and Revival in Judeo-Islamic Culture”, ch. 10 in Schwartz, Great Ages, supra, quotation from p. 241. Compare, e.g., Rustow, Heresy supra fn. 2, at 53-57, explaining that it was only beginning in the 10th century that the Karaites began to trace their origins to the writings of Anan b. David in around 750 CE. ↑

-

We will adopt here the spelling in Robert Brody, Sa’adyah Gaon (Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization; 2013) (first published in Hebrew, 2006). In quoting different sources, however, we will utilize the spellings therein.

For discussion of his name, see the opening footnote in the classic biography by Henry Malter, Saadia Gaon: His Life and Works (Philadelphia: JPS; 1921) (full text available on ‘Google books’). ↑

-

Halkin, “Revolt”, supra fn. 4 in Schwartz, Great Ages, at 244-252. This standard view is reiterated by Raymond P. Scheindlin, who compared Philo of Alexandria (the 1st Cent. CE Jewish-Hellenistic philosopher, living in Alexandria) and Sa’adyah, as follows:

Like Philo (who wrote in Greek), Saadiah wrote in the language of his environment; unlike Philo, Saadiah lived long after rabbinic Judaism had become the mainstream form of Judaism ….

See Scheindlin’s chapter, “Merchants and Intellectuals, Rabbis and Poets: Judeo-Arabic Culture in the Golden Age of Islam”, pp. 313-388 in David Biale, ed., Cultures of the Jews: A New History (NY: Schocken Books, 2002). ↑

-

See, e.g., L. Levine, The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years (New Haven: Yale U.P., 2000) at 503. ↑

-

Ra’anan Boustan, “Rabbinization and the Making of Early Jewish Mysticism”, JQR 101:4 (Fall 2011) at 482-501. See also Stuart S. Miller, At the Intersection of Texts and Material Finds: Stepped Pools, Stone Vessels, and Ritual Purity Among the Jews of Roman Galilee (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; 2nd ed. 2019), referring to “the fifth through eighth centuries” as the “latter-half of Late Antiquity”, at 252 and fn. 11. ↑

-

See fn. 6, supra, at 305. ↑

-

See generally, Robert Brody, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture (New Haven: Yale U.P.; 1998). Brody writes (at 284): “The impetus to systematic theological speculation came to the Jewish world from the outside ….” I will argue herein that Sa’adyah’s writing was motivated by internal Jewish concerns. ↑

-

Marina Rustow, “The Qaraites as Sect: The Tyranny of a Construct”, pp. 149-186 in Sacha Stern, ed., Sects and Sectarianism in Jewish History (Leiden: Brill; 2011), quotations from pp. 161, 165. See also at 167, noting how even the leading student of the Cairo Genizah, S.D. Gotein, “could not rid himself of a model of Jewish history founded on rabbinic authority”. ↑

-

Rustow, supra, fn. 2, at 57 (footnote omitted). ↑

-

Paul Heger, The Pluralistic Halakhah: Legal Innovations in the Late Second Commonwealth and Rabbinic Periods (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003), at p. 344. See also, e.g., at 350, referring to “the total dogmatism of the Geonim.” ↑

-

Thus, Joseph E. David, Jurisprudence and Theology in Late Ancient and Medieval Jewish Thought (Switzerland: Springer; 2014) at 30, summarized:

During the course of the ninth century, the four Sunni legal schools had developed and were shaped as legal communities even beyond the legal realm, as a framework for religious, social and political life. From the tenth century on, as each school began to develop its own legal methodology, the concept was gradually accepted that the four great imams, the founders of the schools, as well as their disciples, had promulgated juridical approaches which were comprehensive, so that all that was left for their successors was the interpretation and application of their teachings. From this arose recognition of the legitimacy of each of the four schools, and the notion that it was permissible for Muslims to be divided among the four. ↑

-

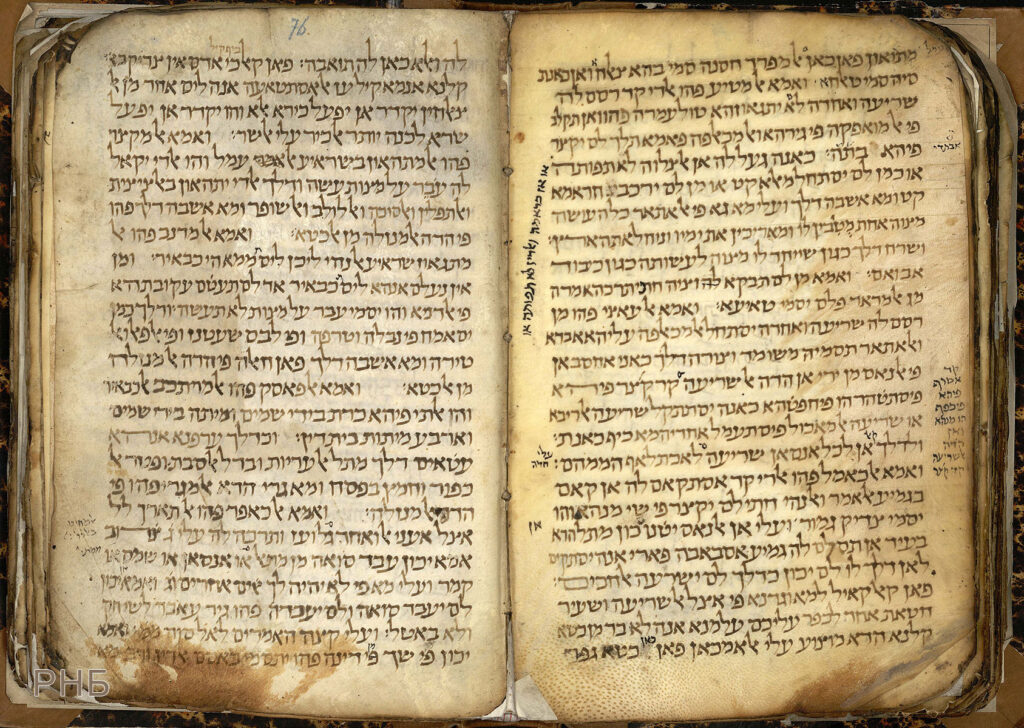

BBO was written in Arabic (but with Hebrew letters), and first translated into Hebrew in 1186. We have utilized the English translation, with introduction and notes, by Samuel Rosenblatt, vol. I of the Yale Judaica Series (New Haven, Yale U.P., 1948). ↑

-

See Sarah Stroumsa, “Saadya and Jewish kalam”, ch. 4 in Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Jewish Philosophy (NY: Cambridge U.P., 2003) at 77-79. ↑

-

See Brody, Sa’adyah Gaon, supra fn. 5, and Malter, Saadia Gaon, supra fn. 5, reviewing Sa’adyah’s output in all these areas. ↑

-

See, e.g., the commentary of Rashi (Rabbi Shelomo Yitzaki, 1040-1105) to Ex. 24:12, citing to a piyyut by Sa’adyah presenting his view of the mitzvot. ↑

-

This essay will not address the broader philosophic issues of how to periodize Jewish history. See generally, e.g., Moshe Rosman, How Jewish Is Jewish History? (Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2007). For present purposes, it must suffice to say that I wish to focus on the lives of ordinary Jews, as a matter of social or ‘cultural’ history, and not just on a ‘history of ideas.’ And I wish to focus on developments ‘internal’ to Judaism, which are not necessarily co-incidental with changes in the identity of the political ruler. ↑

-

See Maristella Botticini and Avi Eckstein, “From Farmers to Merchants”, Boston University, IED Working Papers Series dp – 124 (available on-line), at p. 9. ↑

-

This picture draws upon, e.g.: Adiel Schremer, “The Religious Orientation of Non-Rabbis in Second-Century Palestine: A Rabbinic Perspective,” pp. 319-342 in Zeev Weiss et al., eds., ‘Follow The Wise’ [Festschrift for Lee I. Levine] (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2010); and Ishay Rosen-Zvi, “Is The Mishna a Roman Composition?”, pp. 487-508 in Michael Bar-Asher Siegal, et al., eds., The Faces of Torah [Festschrift for Steven Fraade] (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017); and see also the essays in that volume by Robert Brody and Stuart S. Miller. See also Stuart Miller, At the Intersection, supra fn. 8, esp. in chapters 8 and 11, arguing from the continuation of a “complex common Judaism”, and noting how, e.g., the common/folk practiced in the Landlord of Israel spread to Babylonia, and was first adopted by Geonim in around the tenth century (at 327).

For a discussion of the ‘older’ debate, centered on the thesis of E.R. Goodenough, see Seth Schwartz, “Historiography on the Jews in the ‘Talmudic Period’: 70-640 CE,” ch. 5 in Martin Goodman, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies (Oxford: Oxford U.P., 2002). ↑

-

See Arnon Atzmon, “Literature and Liturgy in Times of Transition: The Piska ‘And It Happened at Midnight’ from Pesikta de-Rav Kahana”, AJS Review 40:2 (Nov. 2016) at 141-160. ↑

-

For a discussion of synagogues in the Land of Israel following the Arab Conquest (in 638), see, e.g., Steven Fine, “Iconoclasm,” BR 16:05 (2000) (Center for Online Judaic Studies). ↑

-

This picture draws upon, e.g., David M. Grossberg, Heresy and the Formation of The Rabbinic Community (Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2017), esp. ch. 1, which expressly builds upon works by Catherine Hezser, Seth Schwartz, Hayim Lapin, Lee I. Levine, Shaye J.D. Cohen, and others.

An important point to keep in mind is that the very term halakha ‑‑ together with various other terms critical to rabbinic Judaism ‑‑ did not exist prior to the rabbinic period. See Steven D. Fraade, “The Innovation of Nominalized Verbs in Mishnaic Hebrew as Marking an Innovation of Concept”, pp. 129-148 in Eliezer Bar-Asher Siegel et al., eds., Studies in Mishnaic Hebrew and Related Fields (New Haven: Yale; 2014) (available on-line).

See also Oded Irshai, “Confronting a Christian Empire: Jewish Culture in the World of Byzantium”, pp. 181-222 in Biale, supra fn. 6, Cultures of the Jews.

See also Naftali S. Cohn, The Memory of the Temple and The Making of the Rabbis (Philadelphia: U of Penn. Press, 2013). ↑

-

On the evolution over time of the ‘Rabbinic Community,’ and in particular the innovation of the Geonim in the direction of uniformity, see, e.g., Moulie Vidas, Tradition and the Formation of the Talmuds (Princeton: Princeton U.P., 2014) ‑‑ see, e.g., at 210, noting that “the authoritative Bavli was part of a Geonic understanding of Rabbinic tradition that was more conservative than the one we find in the Bavli itself.” Similarly, see Joseph E. David, Jurisprudence and Theology, supra fn. 14, at 38-42.

See also Richard Hidary, Dispute For The Sake Of Heaven: Legal Pluralism in the Talmud (Providence: Brown Judaic Studies; 2010). ↑

-

Marina Rustow stresses the importance of the relocation of the Geonic academies from backwater towns to the new center of Baghdad, beginning in perhaps 889/890. See Rustow, “Baghdad in the West: Migration and the Making of Medieval Jewish Traditions”; in AJS Perspectives (Fall 2010) (available on-line). ↑

-

Michael Chernick, in his “Introduction”, at p. 16, to his edited volume, Essential Papers on the Talmud (NY: NYU Press, 1994). Rustow, in Heresy, supra fn. 2, presents a more complex picture of the authority of the Babylonian Geonim, but Chernick’s basic point remains, I suggest, accurate. ↑

-

See, e.g., Lawrence A. Hoffman, The Canonization Of The Synagogue Service (South Bend: U. of Notre Dame Press, 1979). ↑

-

This is not to say that Sa’adyah ‘defeated’ the Karaites ‑‑ for the historical record shows that the Karaites continued to flourish. See, e.g., Rustow, Heresy, supra fn. 2, at 20. Sa’adyah’s polemics many have assisted, however, in defining the boundaries of the Rabbanite approach, by grouping all opposing pictures under the label of ‘Karaite.’ ↑

-

Thus S.D. Goitein wrote in A Mediterranean Society ‑‑ An Abridgement in One Volume (Berkeley: U. of Cal. Press, 1999) (revised and edited by Jacob Lassner), at 199-200:

the deep theological problems that had occupied the Islamic world and the Jewish community within during the eighth through the tenth century had either been settled or at least clarified; the battle lines between conflicting views and practices (within Judaism, for instance Karaites against Rabbanites) had been drawn: one knew where one stood, what to believe and how to act. The eleventh and twelfth centuries were comparatively sedate. Few new questions were asked, and there were answers to those that were. ↑

-

See, e.g., Rustow, “The Qaraites as Sect”, supra fn. 11. ↑

-

See Sarah Stroumsa, “Saadya and Jewish kalam”, supra fn. 16. ↑

-

See the very nice account by Michael Rohlf, for the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Kant, § 2. ↑

-

Of course, we generally recognize today that there is something inherently problematic about, e.g., a ‘philosophic’ argument that attempts to ‘prove’ the immortality of the soul. This was, however, the subject of Moses Mendelssohn’s first work, based on which he rose to fame throughout Europe. See ch. 10 in Zachary Alan Starr, Toward A History of Jewish Thought: The Soul, Resurrection and the Afterlife (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock; 2020). ↑

-

Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (NY: Basic Books, 1974), at xiii. ↑

-

Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity (NY: Schocken [Nextbook]; 2006), at 48-63. ↑

-

See Warren Zev Harvey, ”Saadiah, Mendelssohn, and the Theophratus Thesis”, in Raphael Jospe, ed., Paradigms in Jewish Philosophy (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson U.P., 1997) at 60-69. ↑

-

It appears that the concept of double reward derives, for Sa’adyah, from the reference in Isaiah 40:10 to both “reward” and “recompense”. Contextually, as a matter of poetry, the two terms stand in parallelism; but it was a familiar midrashic technique to disregard the poetic form, and to instead give separate significance to each element of the poetic ‘doubling’. See generally James Kugel, The Idea of Biblical Poetry: Parallelism and its History (New Haven: Yale U.P., 1981); see ch. 3, titled “Rabbinic Exegesis and the ‘Forgetting’ of Parallelism”.

Heinemann notes this concept of double-reward as a critical first step in Sa’adyah’s approach to the mitzvot, but does not otherwise explicate this point (at 52). Compare, however, his concluding comment (at 56): “Saadia’s explanation is indeed apt to counter the stumbling blocks that were the bane of the Arab skeptics and their Jewish students, ….” Isaac Heinemann, The Reasons For The Commandments In Jewish Thought; From the Bible to the Renaissance (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2008) (Leonard Levin, tr.) (originally published in Hebrew, 1953).

A double reward is mentioned in the version of the saying of Antigonus of Sokho as preserved in Avot d’Rabbi Nathan, in contrast to the version preserved in Pirkei Avot 1:3; see below fn. 46. That addition may be later than Sa’adyah.

A ‘double reward’ is also mentioned, in a Messianic context, in Zachariah 9:12; cf. Isaiah 61:7.

The idea that one who performs a good deed without having been commanded receives a lesser reward than the person who performs that deed because he or she was commanded is set forth in b.Avodah Zarah 3a; and b.B.K 38a; see esp. b.Kiddushin 31a, telling the story of a righteous gentile who is rewarded for honoring his father, and concluding by teaching, how much more so will we be rewarded, who have been commanded. ↑

-

See Michah Gottlieb, Faith and Freedom: Moses Mendelssohn’s Theological – Political Thought (Oxford: Oxford U.P., 2011) at 152-153 fn. 181, comparing Mendelssohn and Sa’adyah, as follows (internal citations omitted): I find at least ten similarities between Saadya and Mendelssohn: (1) Both stand at the beginning of traditions of Jewish philosophy. (2) Both have wide ranging intellectual interests including philosophy, biblical translation and exegesis, grammatical work, poetry and religious polemics. (3) Both write philosophy in a popular vein seeking to enlighten the masses and elite alike; (4) Both are philosophical eclectics who do not adhere to a single school of philosophy; (5) Both are epistemological optimists who think that reason can establish the basic principles of morality and metaphysics and that reason and revelation are in fundamental harmony with one another. (6) Both see God’s creation of the world as expressing His goodness and both adopt an anthropocentric view which makes human happiness/perfection the purpose of creation; (7) Both are “eudamonic pluralists” who see cultivation of intellect as a component of perfection, but not the exclusive or even the highest form of perfection; (8) Both have a halakhic-centered concept of Judaism with Saadya writing that Jews are a nation by virtue of their laws (shariah) and Mendelssohn describing what distinguishes Judaism as “revealed legislation.” (9) Both think that reason alone is insufficient to stir one to action, which is why the Bible employs parables and striking imagery. (10) Both see the public nature of biblical miracles as evidence of the superior reliability of Judaism over other faith traditions.

There are, of course, notable differences between the two such as Saadya’s claiming that while moral and religious truth are knowable by reason in principle, in practice it would take a long time to work these teachings out which is why revelation is needed, and Saadya’s affirming eternal punishment. Mendelssohn rejects these views as incompatible with divine goodness.

See also Louis Jacobs, A Jewish Theology (NY: Behrman House; 1973) at 310-312, sharply criticizing Sa’adyah’s belief in eternal punishment. ↑

-

See Marc Herman, “Prophetic Authority in the Legal Thought of Saadia Gaon”, JQR 108:3 (Summer 2018), at 271-294. See also Joseph David, Jurisprudence, supra fn. 14, at 89-93 and 155-157. ↑

-

Compare Starr, The Soul, supra fn. 34, at 109 (“The rabbis were little concerned with clarifying any issues relating to resurrection such as explaining the nature of the resurrected body” ‑‑ as opposed to their concern to show the Biblical basis for the doctrine), with id. at 140-441, reviewing Sa’adyah’s detailed discussion in BBO as to how, at a first stage, the resurrected bodies/souls “will be able to eat, drink, and marry (have sexual relations)”. ↑

-

See generally Alfred Ivry, “Providence, Divine Omniscience, and Possibility: the Case of Maimonides”, pp. 175-191 in Joseph A. Buijs, ed., Maimonides: A Collection of Critical Essays (South Bend: U. of Notre Dame Press, 1998). ↑

-

See Stroumsa, “Saadya and Jewish kalam”, supra fn. 16, at 73-74. Cf. Koran ch. 55 vs. 41, 56-57, 78. ↑

-

See also Starr’s discussion concerning resurrection in the rabbinic literature relative to Sa’adyah, in footnote 41, supra. ↑

-

Translation by Jonathan Wyn Schofer, The Making of A Sage: A Study in Rabbinic Ethics (Madison: U. of Wisconsin Press; 2005) at 154; brackets by Schofer. ↑

-

A later ‘revision’ of the maxim of Antigonus of Sokho, as reported in the work known as Avot d’Rabbi Nathan (“ARN”) (known in two versions, ‘A’ and ‘B’), adds that the righteous can and should expect a double reward in the world to come. (Also, the sense of ‘slaves’ is transformed by context.) Per the translation of Schofer, supra (at 155), the ARN version reads as follows:Antigonus of Sokho received from Simeon the Righteous. He would say: Do not be like slaves/servants [‘abadim] who serve the master for the sake of receiving a food allowance [‘al menat leqabbel peras]. Rather, be like slaves who serve the master not for the sake of receiving a food allowance, and let the fear of Heaven [mora’ shamayim] be upon you, so that your payment [śekharkhem] will be doubled in the world to come. (A5, 25-26; also B10, 25-26; emphasis added)

The date when this last line was added is very unclear: Schofer notes generally [193 fn. 14] that “it is very possible that important elements in the compilation of Rabbi Nathan occurred during the early Geonic period”. See also id., at 157, noting that the additional material in Version ‘B’ may reflect theological debate “in late antiquity or the early medieval period”.

Clearly, however, this last line was added after the tradition was recorded, in the following paragraph of ARN, as to how disciples of Antigonus thought that Antigonus was denying the existence of a world-to-come; and so those disciples became the founders of two ‘Second Temple’ heresies, in opposition to the teachings of the Pharisees. If the two students described in ARN had heard the teaching about a double-reward, they would not have been confused, and the story of their confusion would make no sense.

Schofer concludes his discussion by suggesting that the rabbis overall indeed intended the ‘original’ teaching of Antigonus to represent the highest level of faith (at 159-160):

We can identify, then, three different modes of comportment before the deity that rewards and punishes: (1) serving God to receive payment (self interest); (2) serving God to receive payment not in this world but in the next (deferred self-interest); (3) serving God only through love and fear. The text does not arrange these types as such, but implicit in the material may be a hierarchy moving from self-interest to deferred self-interest to consciousness in which motivation and emotion are centered on the deity and not on reward. ↑

-

See, e.g., Ephraim E. Urbach, The Sages (Cambridge, MA: Harvard U.P, 1987) (translated by Israel Abrahams) (first published in Hebrew, 1969) at pp. 400-408. For a contemporary approach along these lines, see Martin S. Cohen, Spiritual Integrity: On the Possibility of Steadfast Honesty in Faith and Worship (Lanham: Hamilton Books; 2021). Cohen discusses Antigonus of Sokho at p. 132. ↑

-

Abraham Joshua Heschel, Heavenly Torah as Refracted Through The Generations (NY: Continuum, 2005) (edited and translated by Gordon Tucker), at 271, quoting from Sifre, ch. HaBerakha, 346.

See generally Dov Weiss, “The Rabbinic God and Medieval Judaism” Currents in Biblical Research 15:3 (2017) at 369-390. ↑

-

Id., referring to b.Berakhot 6a. ↑

-

Id. at 271, quoting from M. Makkot 3:16, in the name of Rabbi Hananiah ben Akashya. ↑

-

Rabbi Judah the Pious died in 1217, and his key disciple, Rabbi Eleazar ben Judah ben Kalonymus of Worms, died in around 1230. While they did not have the ‘philosophic’ translation into Hebrew of BBO published by Judah ibn Tibbon, they knew BBO through an Eleventh Century poetic paraphrase. See Joseph Dan, “Ashkenazi Hasidim and the Maimonides Controversy” (first published in 1992), ch. 8 in his collection, Jewish Mysticism in the Middle Ages (Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1998), at 187. See also Ronald Kiener, “The Hebrew Paraphrase of Saadiah Gaon’s ‘Kitab al-Amanat wa’l “P’tiadat” A.J.S. Review 11:1 (Spring 1986) pp. 1-25. In Kiener’s underlying PhD thesis, proffering a critical edition of the first five chapters of the paraphrase of BBO, the discussion of “double reward” appears at pp. 123-124. Interestingly, as Salo Baron noted in his forward (at vii) to Zvi Ankori, Karaites in Byzantium: The Formative Years 970-1100 (NY: Columbia U.P., 1959), there apparently were no Karaites in early Ashkenaz ‑‑ leading to the question, why not? An attempt to answer is beyond the scope of the essay.

As one hypothesis, however: Islam did not claim for itself the text of ‘our’ Tanakh ‑‑ to the contrary, Islam regarded our text as defective and corrupted. By contrast, Western Christendom endorsed ‘our’ text; and indeed sought to use ‘our’ Tanakh to convince us to convert. Ashkenazi Jewry opposed those efforts by insisting that God’s covenant included both the written text and the Oral Torah ‑‑ so that study of the Oral Torah (as then set down in writing) became an act of resistance. (See, e.g., Midrash Tanhuma, Vayera, 5; parallel to Pesikta Rabbati 5, where Moses is told that the reason that the Mishnah was not being conveyed to him in written form was so that the other nations would not be able to appropriate it and claim to thereby possess the covenant.)

The Karaite focus on scripture, as opposed to the Oral Torah, could not, I suggest, provide the necessary resistance to Western Christendom. ↑

-

See generally, e.g., Adiel Schremer, “Religious Orientation”, supra fn. 21. ↑

-

In one of the early debates concerning homosexuality in Conservative halakha, Ismar Schorsch, Chancellor of JTS ‑‑ in rebuttal to a leading ‘liberal’ rabbi, Harold Schulweis – declared:

We are no longer biblical but Rabbinic Jews, the products of a religious culture that has made of intertextuality a sacred dialogue and exegesis a way of thinking.

Ismar Schorsch, “Marching to the Wrong Drummer”, Conservative Judaism 45:4 (Summer 1993) at 19, quoted in Edward Feinstein, In Pursuit of Godliness and a Living Judaism: The Life and Thought of Rabbi Harold M. Schulweis (Nashville: Turner Publishing; 2019) at 222-223.

Perhaps, however, there are possibilities beyond Schorshch’s picture. ↑