For a Formatted PDF of this article, click here.

JACOB’S HOPE FOR SALVATION: THE EXTRAORDINARY CAREER OF GENESIS 49:18[1]*

David Arnow

In the midst of Jacob’s deathbed testament, the patriarch utters three words as an apparent aside:

I hope for Your salvation, O Lord! [2]

. לישועתך קויתי יהוה

Over the millennia, this three-word verse has enjoyed a surprising history. Traces of that history can be found in contemporary prayer books. In the prayer to be recited at bed time, the Conservative Movement’s Siddur Sim Shalom calls for reciting the verse in three permutations.[3] Prayer books published by the Reform Movement omit this practice, although some Reform synagogues that have published their own prayer books have included it.[4] Prayer books used by Orthodox congregations, such as Philip Birnbaum’s Daily Prayer Book (hereafter, Birnbaum), include other customs involving this verse as well. In the daily morning liturgy, following Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles, Birnbaum calls for reciting three permutations of the verse in both Hebrew and Aramaic.[5] Other prayer books also prescribe permutations of the verse to follow the Wayfarer’s Prayer.[6] No other biblical verse in the prayer book is recited in this manner.[7] The verse also appears—without permutations—in a modified form in the fifteenth blessing of the weekday Amidah which begins, ‘את צמח דוד’ “Cause the progeny of David, Your Servant, to Blossom,” as discussed below. It can also be found in the circumcision liturgy, and again, in Birnbaum, among a series of verses to be recited after dressing in the morning.[8] In addition, for centuries, it was said upon sneezing.

What explains the unique treatment and extensive usage of Genesis 49:18? This article attempts to answer those questions through an exploration of its history in Jewish magic, mysticism, and liturgy. But first, we must consider the biblical context of our verse, and its appraisal in modern biblical scholarship and its interpretation by classical commenters.

BIBLICAL CONTEXT AND COMMENTARY

The verse appears toward the middle of Jacob’s deathbed testament.

Dan shall govern his people,

As one of the tribes of Israel.

Dan shall be a serpent by the road,

A viper by the path,

That bites the horse’s heels

So that his rider is thrown backward.

I hope for Your salvation, O Lord![9]

Modern biblical scholarship generally holds that our verse was likely a later addition to Jacob’s testament. Raymond De Hoop, who has written the most extensive analysis of Jacob’s testament, concludes: “The insertion of this line might betray an early liturgical setting of our text, where the prediction of Dan attacking his enemies is followed by the prayer for God’s salvation, derived from the Psalms.”[10] Sarna comments that “the formulation corresponds to well-established liturgical patterns” with similar key words, as in Isaiah 25:9; 33:2 and Psalms 25:5. Sarna also makes a critical observation that needs to be kept in mind as we explore the subsequent use of our passage in magic, mysticism and liturgy: “Such a prayer would only originate in a situation of danger.”[11]

Indeed, a review of the Tanakh as a whole confirms the tribe of Dan’s particular vulnerability. The theme is apparent as early as the book of Numbers (10:25), which states that, when the Israelites journeyed through the desert, the tribe of Dan came at the very end of the assemblage and served as a rear guard.[12] In subsequent periods, Nahum Sarna writes:

There is much evidence, however, that during the settlement period Dan was a small tribe in a precarious position… The genealogies of Chronicles ignore the tribe altogether… Very significantly, the Book of Joshua does not define the borders of the tribe. These are inferred from those of the neighboring tribes… There are no reports of the Danites having captured any of their allotted cities. In fact, the term “the Camp of Dan”—Hebrew mahaneh dan—in Judges 13:25 (cf. 18:12) shows that they occupied a fortified camp, not a true settlement, between the two Canaanite cities of Zorah and Eshtaol. All attempts on the part of the Danites to settle in the Valley of Aijalon and in the Shephelah were unsuccessful, and they finally despaired of gaining their originally assigned territory and migrated northward. . .[13]

Against this background, the apparent connection in the existing text between the hope for God’s salvation and the tribe of Dan, acquires added urgency. With regard to Jacob’s death or Dan’s future troubles, the association of Gen. (Genesis) 49:18 with circumstances of vulnerability—a theme that will recur throughout this article—emerges quite clearly from the biblical text itself.

However, a number of Jacob’s “blessings” envision violent interactions between a son or that son’s tribe and future enemies. For example, an expression of hope in God’s salvation could equally have been added to Gad’s “blessing,” which immediately follows that given to Dan: “Gad shall be raided by raiders, but he shall raid at their heels” (Gen. 49:19). (Note that the traditional line spacing in the Torah itself, makes it clear that Gen. 49:18 was traditionally viewed as being associated with Dan’s “blessing,” a fact obscured by some contemporary printed versions of the Hebrew Bible [e.g., the JPS Tanakh] in which the verse is set off as an independent paragraph.)

So, the question remains: why was our passage added to Jacob’s blessing of Dan in particular? Although we may never have a definitive answer to this question, there is an important connection between our verse and the tribe of Dan which might account for why the words we now recognize as Gen. 49:18—“I hope for your salvation, O Lord”—found their way to Jacob’s “blessing” of Dan. The connection derives from a passage in Jeremiah (8:15-17): “15We hoped for good fortune, but no happiness came; for a time of relief—instead there is terror! 16The snorting of their horses was heard from Dan; at the loud neighing of their steeds the whole land quaked. They came and devoured the land and what was in it. 17Lo, I will send serpents against you, adders that cannot be charmed and they shall bite you—declares the Lord.” קוה לשלום ואין טוב לעת מרפה והנה בעתה: מדן נשמע נחרת סוסיו מקול מצהלות אביריו רעשה כל־הארץ ויבואו ויאכלו ארץ ומלואה עיר וישבי בה: כי הנני משלח בכם נחשים צפענים אשר אין־להם לחש ונשכו אתכם נאם־יהוה. In this passage, Jeremiah alludes to God’s wrath at the sinful Northern Kingdom of Israel, and its ensuing destruction in 722 BCE. The people had hoped for peace, but instead reaped terror. The cataclysm began with an invasion of the northern most tip of Israel, then home to the tribe of Dan.

The second and third verses in the passage from Jeremiah share a number of key words with Gen. 49: 16-17, the first two verses of Jacob’s “blessing” of Dan. In addition to the name ‘Dan,’ both passages refer to horses, serpents, and biting ((סוס, נחש, נשך. Indeed, these are the only two narrative passages in the Bible that share these key words in such close proximity. (I say narrative passage, because the words, snake, horse and biting, occur in close proximity Eccl. 10:7, 8, and 11, but these are a series of independent aphorisms.) In Genesis, the tribe of Dan is likened to a venomous snake that attacks the heel of an approaching enemy’s horse. In Jeremiah, horsemen invade Dan’s territory and God sends poisonous snakes to attack the Danites. Reflecting the Bible’s common measure for measure mode of punishment, what Dan and his tribe were to have done to others (in Genesis), will now be done to them (in Jeremiah), in retribution for their faithlessness. It seems clear that whoever added Gen. 49:18 to Jacob’s “blessing” of Dan was familiar with this section of Jeremiah. The decision to tack on the words that now comprise Gen. 49:18 to Dan’s “blessing,” reflects a keen inter-textual awareness. The addition of Gen. 49:18 adds two more keywords found in the Jeremian passage to the patriarch’s “blessing” of Dan: hope and Adonai.(קוה, יהוה) In Jeremiah, the faithless northerners have lost hope. The addition of Gen. 48:18 casts Dan in a more favorable light, reaffirming the tribe’s hope in God’s ultimate salvation. As the language in Jeremiah doubtless reflects awareness of Gen. 49:16-17, so too does the placement of Gen. 49:18 clearly indicate knowledge of Jeremiah.[14]

Turning briefly to classical commentators, suffice it to say that the ambiguity surrounding the passage has raised numerous questions. Is Jacob’s strength failing, and is he hoping that God will hasten his end and deliver him from suffering? Is Jacob hoping that God will save Dan? Jacob has compared Dan to a viper by the road, who bites a passing horse’s heels and then risks being killed by the rearing horse. Do these words come from the mouth of Dan, who sees in the picture that Jacob has painted of him such vulnerability that he (Dan) calls to God for help? Or does Jacob’s comment come as his (Jacob’s) own reaction to his prophetic vision of the tragic future of Samson, Dan’s famous descendent? Commentators have argued for each of these interpretations, and others as well, that seek to find additional parallels between Jacob’s words to Dan and the tribe’s difficult future.[15]

Even the plain meaning of the verse is not free from ambiguity. The great majority of commentators read Gen. 49:18 as if it were an expression of hope that God will provide salvation. But the Hebrew equally supports an entirely different reading. “I hope for Your salvation, O Lord.” “Your salvation” can mean the salvation by God, as we generally read it, or as salvation of God. Moses Alshekh (1508–1593, Safed) preferred the latter reading. The hope is not that God will redeem us, but that God will be redeemed.[16] Alshekh pointed to the tradition in Jewish thought that sees God and humanity both in need of redemption, both dependent for salvation on one another. For example, an 11th or 12th century midrash chides Israel for asking Balaam, the oracle in the Book of Numbers, when Israel’s redemption will come. In the midrash, God says that Israel should be more like Jacob, who said, “I hope for Your salvation deliverance, O Lord!” Likewise, continues the midrash, Isaiah says, “’For soon My salvation shall come’ (Isaiah 55:1). It doesn’t say your salvation, but My salvation… For had not the verse explicitly said so, it would not have been possible to say it!”[17]

For all the richness of their discussion, the classic commentators remain silent, however, about what may be the three most distinguishing features of the verse: it contains the first occurrence in the Bible of this word for salvation (the root is ישע); the first occurrence of hope (the root is קוה); and these are the last words that Jacob addresses to God. The terse combination of God, salvation and hope gives the verse extraordinary potency, and may help account for the grip it has had in magic, mysticism, and liturgy, which we will now explore.

A MAGICAL/MYSTICAL VERSE, AND THE DIVINE NAMES IT CONTAINS[18]

Recent scholarship has done much to recover the lost texts—including amulets and incantation bowls—of ancient Jewish magic and their significance, and to explain the role of magic in the lives of Jews beginning in the Greco-Roman period and continuing to our day. [19]

According to The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism, “Perhaps the most frequently used [biblical] verses in a theurgic context are Genesis 49:18, Zechariah 3:2, and Numbers 6:24–26.”[20] (The author of this work distinguishes theurgy from magic. The former requires “spiritual and moral excellence” of the practitioner, while the latter does not. The theurgist seeks power, to influence figures such as God, demons, or angels whereas the magician seeks to influence impersonal, abstract forces.)

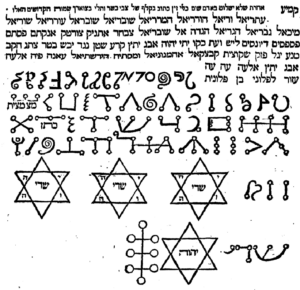

Let’s begin our foray into the world of magic with a look at two medieval amulets, one among the most unusual, and the other perhaps the most common.[21] Below is an amulet thought to have been composed by Eleazar ben Judah of Worms (c. 1176–1238), also known as Eleazar Rokeach, the last major member of the group of pietists known as Hasidei Ashkenaz;. At the top, it states that the amulet affords protection against an enemy’s weapons; but the meaning of many of its symbols is unknown. (During this period, the six-pointed star, now called the Star of David, was a magical, mystical symbol that enjoyed no greater significance than the five-pointed star, which also appeared frequently in Jewish and other magical texts.[22]) Amidst a list of names of angels, the verse appears in the form of a divine name.[23] As we will see later, many complex divine names were derived from this. In this case, however, the derivation of the Name is rather straightforward. The first two words of the verse are sequentially taken in triads to create four words which are followed by the tetragrammaton as it appears in the verse.

The result is ליש ועת כקו יתי יהוה (as visible in the fourth line).[24]

Figure 1: From Sefer Raziel Ha-Malakh (ספר רזיאל המלאך), 1701, Amsterdam, p. 44b, attributed to Eleazar ben Judah of Worms, c. 1176–1238, (public domain per Wikipedia). Note the fourth line.[25]

Shorshei HaShemot (שרשי השמות), a compilation of divine names, notes that one should direct one’s thoughts to this name when reciting the verse, so that its power may accompany one on a journey.[26]

The next amulet, one of the most widespread, is often called the ‘Menorah Psalm.’ The amulet uses the words of Psalm 67 to depict a seven-branched menorah, and has been used in various contexts to provide protection—on the doors of arks in synagogues, in prayer books, in calendars for counting the Omer, etc. When the Menorah Psalm is accompanied by Psalm 16:8 (beginning with Shivviti Adonai lenegdi tamid [שויתי יהוה לנגדי תמיד] “I am ever mindful of the Lord’s presence”), it is known as a shivviti or a shivviti menorah, and, in certain pious neighborhoods, it is ubiquitous.[27] The amuletic menorah exists in many different forms, and has a long and fascinating history in its own right. In brief, that history reaches back to Sefer Abudarham (ספר אבודרהם), written in 1340 by David Abudarham (דוד אבודרהם), the earliest known source to ascribe benefits to reciting the Menorah Psalm daily.

Figure 2: Siddur of Yehiel Beth El (Pisa, 1397). Photograph courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Available online in a catalogue of 14th century menorahs.

To one who recited the Menorah Psalm, it would be counted as “lighting the pure Menorah in the Holy Temple,” and one would thus be graced to see the face of the Shekhinah (the Divine presence). Abudarham also explains the relationship between the Psalm and the menorah. Excluding its dedicatory verse, the Psalm includes seven verses and a total of forty-nine (7 x 7) words, seven in each verse.[28] The earliest known image of the Menorah Psalm dates back to a manuscript of a prayer book from Pisa that dates back to 1397 (see above). At the base of this drawing, Gen. 49:18 appears (once, without permutations, written in triads) above the expression barukh shem kevod malkhuto le’olam va’ed (ברוך שם כבוד מלכותו לעולם ועד, “Blessed is the Name of His glorious kingdom forever”), a paraphrase of Psalm 72:19, which is generally recited silently after saying the Shema. This siddur (סדור, ‘prayer book’) recounts that, when King David went out to battle, his shield bore a golden plate with the Menorah Psalm (and presumably Gen. 49:18 and the paraphrase of Psalms 72:19). David would concentrate on its secrets and, as a result, vanquish his enemies.[29] Note that Gen. 49:18 is written out in the same manner as we found in the previous amulet. Given the power of this divine name described by Eleazar ben Judah of Worms—the power to protect against the weapons of one’s enemies—its presence on David’s shield makes perfect sense.[30]

The custom of including both of these expressions near the base of the Menorah Psalm was widespread, as was the custom described above to regroup the letters of Gen. 49:18 to form a powerfully protective divine name.[31] Important examples include the illustration of the Menorah Psalm in Menorat Zahav Tahor (The Menorah of Pure Gold), Solomon Luria’s frequently reprinted 1581 kabbalistic interpretation of the amulet, and the early 17th century doors from Moses Isserles’ synagogue in Cracow.[32] On the amuletic powers of the Menorah Psalm, Luria wrote this:

ואמרו חכמים בעלי הקבלה כל מי שיראה זה המזמור כל יום מצוייר בצורת המנורה, ימצא חן ושכל טוב בעיני אלהים ואדם, אם הוא מצוייר על ארון הקודש יגן בעד גזירה רעה לקהל.

And the sages wise in the Kabbalah said: Everyone who will see this psalm every day, drawn in the form of a menorah will find grace and understanding in the eyes of God and of people, and, if it is drawn on the Holy Ark, it will protect the community from an evil decree.[33]

Why did Gen. 49:18 find its way into Menorah Psalm amulets? Even if we assume that the verse contained a powerful divine name, the question remains: Why was this particular divine name chosen for the base of the Menorah Psalm? With countless divine names to choose from, why pick this one? Solomon Luria offers a highly complex Kabbalistic rationale—relating to the unification of upper and lower sefirot[34]—but this interpretation may have had little to with the original motivation to bring Gen. 49:18 into the Menorah Psalm. A simpler explanation may lie in the facts that the verse speaks of hope and salvation and that, since antiquity, the menorah has been a symbol of both. Scholars believe that this explains the widespread use of designs of the menorah in catacombs and on sarcophagi in which Jews were buried, a custom that was common in medieval times and that can still be observed on a number of Jewish tombstones today.[35] In any case, it is noteworthy that in many older drawings of the Menorah Psalm, Gen. 49:18 forms an important part of the menorah’s base. Jacob’s last words to God provide the foundation, as it were, for subsequent Jewish expressions of hope and salvation.

Although the Menorah Psalm generally features Gen. 49:18 written out in full, occasionally it is abbreviated with the first letters of each word in Hebrew and Aramaic.[36] This custom is also common in other amulets using the verse. Schrire notes that Hebrew and Aramaic abbreviations of Gen. 49:18 commonly appear on amulets used for general safety and good fortune, as well as protection of the mother and child during and after birth. His study includes at least half a dozen examples.[37] Sometimes the verse appears on amulets in conjunction with divine names used to ward off demons or to bring about some other desired outcome. The combination of the first letters of each word of Gen. 49:18— lamed, kuf, yod in Hebrew, or lamed, samech, yod in Aramaic (לפורקנך סברית יי) —comprise divine names themselves, as do permutations of those letters. Anagrams of these three letter names are often found in amulets and incantations.[38] (See Figure 3 below.)

Something related also appears in Isaiah Horowitz’s (c. 1555-1630, Prague and Israel) Kabbalistic commentary on Gen. 32:11. The night before encountering his brother Esau, Jacob divided his camp in two and crossed over the Jordan River “with my staff alone” (כי במקלי, ki vemakli). Horowitz alludes to a midrash claiming that, as a result of Jacob’s merit, God prevented the angel Samael (סמאל) from attacking him. Horowitz explains the midrash through an examination of the divine names present in the phrase כי במקלי. Rearrange the first four letters (כ י ב מ) and you have an allusion to one divine name, ,מכב״י which corresponds to the first letters of the first four words of Exodus 15:11, “Who is like You, Adonai” (מי כמכה באלים יהוה, mi khamokha ba’elim Adonai). Rearrange the remaining letters of כי במקלי–ק ל י—and you have the other Name, לק”י—the name based on Gen. 49:18 found so frequently in amulets and incantations.[39]

Figure 3: Amulet case, Iran, 18th–19th century, HF 0804, 103/433. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, The Feuchtwanger Collection, purchased and donated by Baruch and Ruth Rappaport, Geneva Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem by Yair Hovav. Used with permission from the Israel Museum. Discs feature לקי and לסי, the Hebrew and Aramaic divine Names composed of the first letters of the words in Gen. 49:18.

Gen 49:18 also became a fertile source for creating complex divine names derived from various methods of creating permutations of its letters. Divine names that include complex letter permutations probably reflect early mystical practices based on the belief that creating or reciting letter permutations induces an altered state of conciseness which facilitates ecstatic encounters with the Divine on the highest possible level.[40] One such name appears in connection with a prayer composed by Rabbi Meir Paprish (1624–1662, a kabbalist who lived in the land of Israel) to be recited before studying Kabbalah. The prayer calls for repeating Genesis 49:18 in three different orders twice, in order to yield two names of God comprised of sixteen triads.[41] According to the prayer, the purpose of reciting these two names is to assure that nothing learned or revealed in the course of study will be forgotten, and that divine name itself will remain a source of fear that prompts one to do God’s will.

This name served other purposes as well. Shorshei HaShemot, a compendium of divine names, explains that one can invoke the power of this name at night to calm a crying child by whispering it in the child’s ear. The ritual also calls for whispering a verse from Isaiah: “כי־עם בציון ישב בירושלם בכו לא־תבכה חנון יחנך לקול זעקך כשמעתו ענך.” “Indeed, O people in Zion, dwellers of Jerusalem, you shall not have cause to weep. He will grant you His favor at the sound of your cry; He will respond as soon as He hears it” (Isaiah 30:19).[42]

Having explored the use of Gen. 49:18 in amulets and divine names, let’s consider how it has been used in incantations—with one example from the ultra-pietistic world of mystical Hasidism, and another from the realm of folklore. Thought to have been published in 1915, Sedei Besamim (שדה בשמים) is a compendium of Kabbalistic incantations culled from mystical sources over the generations. The frontispiece states that, if ten Jews recite these properly early in the morning, it will break down all the barriers between God and the people of Israelת and will turn away God’s harsh decrees. The incantations, many of which contain divine names, should be concentrated upon internally, not recited aloud. One incantation follows this verse: “והסיר יהוה ממך כל־חלי וכל־מדוי מצרים הרעים אשר ידעת לא ישימם בך ונתנם בכל־שנאיך.” “The Lord will ward off from you all sickness; He will not bring upon you any of the dreadful diseases of Egypt, about which you know, but will inflict them upon all your enemies” (Deut. 7:15). The incantation calls for threefold recitation of several biblical verses that refer to hope. It then includes six permutations of Gen. 49:18, written out as it appears on the Menorah Psalm to form divine names, and six permutations of the verse in Aramaic. Even in this book of incantations, the treatment of Gen. 49:18 is unique.[43]

Turning to folklore, Eastern European incantations made use of the verse to ward off the evil eye. Regina Lilienthal (1857–1924), a noted Polish scholar of Jewish folklore, collected this example:

By this upper eye I command all of you to turn away and depart and flee from this house and from this district and from so-and-so son of so-and- so. And may you have no power over so-and-so son of so-and-so, neither by day nor by night, neither waking nor dreaming, in none of his 248 limbs and 365 sinews, and may he be protected and closed about and guarded and watched and delivered and saved, as is written: “See, the guardian of Israel neither slumbers nor sleeps!” (Ps. 121:4).[44]

The incantation concludes with three permutations of Gen. 49:18, in both Hebrew and Aramaic.[45]

While some rabbis from those times looked askance at these practices—i.e. both amulets and incantations—contemporary scholars view them with a measure of sympathy. Theodore Schrire, who studied the use of amulets by Jews from Middle Eastern countries, wrote:

The texts of kameoth [amulets] turn out to be an expression of faith and hope of… orthodox Jews using formulae that have been derived from the Bible… and which often appear in the Liturgy. . . [T]hey were appeals to the Almighty from a group of people in sore personal difficulties. . . It seems a far cry from these innocent expressions of faith, devotion and hope to the defiance and… [heresy] that has so often been ascribed to their users.[46]

Without diminishing this view of the relationship between magic and devotional evocations of hope, it is worth observing that some scholars take issue with the fact that Jewish amulets and incantations merely make use of verses that are already liturgically familiar. The relationship may go in the other direction. As Maureen Bloom notes, “the efficacy of a phrase in an incantation could well have given rise to the use of the same phrase in prayer.”[47] At least with respect to Gen. 49:18, the liturgical customs involving the verse seem to have migrated from their use in earlier magical practices, although this migration occurred when the boundary between prayer and magic was fluid in any case. It is to the liturgical customs utilizing our verse that we will now turn.

A LITURGICAL FAVORITE

Before beginning this section, two notes are in order. First, our discussion of the liturgical uses of Gen. 49:18 will rely on those found in Avodat Yisrael, the Ashkenazic siddur edited by in 1868 by Seligman Isaac Baer (1825–1897).[48] This siddur has been both popular and influential. The Encyclopaedia Judaica asserts that it “has been accepted as the standard prayer book text by most subsequent editions of the siddur.”[49]

Second, as we survey examples of Gen. 49:18’s liturgical appeal, the legacy of its uses in the world of magic, and the power of Divine names it was believed to contain, will become clear. But it is worth remembering something else that may help explain its popularity. As noted by Michael Weizman, Jewish liturgy in general avoids biblical verses that give voice to complaints to God about one’s personal condition. Instead of this, prayers express more general appeals for God to provide salvation. Indeed, it is fair to say that after praise of God—and often directly following such praise—requests for divine salvation constitute Judaism’s second most frequent liturgical motif.[50] The frequent liturgical use of Psalm 20:10—יהוה הושיעה המלך יעננו ביום קראנו (“God save! May the King answer us when we call”)—is but one of many examples of this. The fondness for en. 49″aing answer us when we call.”ular e general appeals for God to provide salvation when called upon to do so. This helps Gen. 49:18 reflects the same sensibility.

THE BEDTIME PRAYER[51]

Let’s begin our exploration of liturgical customs involving Genesis 49:18 with the prayers before retiring for bed, Keri’at Shema Al HaMittah (קריאת שמע על המטה). Contemporary traditional prayer books call for reciting permutations of the verse three, six, or nine times, depending on the siddur. [52] The origins of the bedtime Shema reflect the extreme sense of vulnerability associated with retiring for sleep at night. According to the Talmud, “Anyone who recites the Shema in his bed [before going to sleep]—demons keep away from him,” and, “if one recites the Shema on his bed, it is as if he is holding a two-edged sword.”[53] The Talmud also observes that sleep is one sixtieth part death.[54]

When did Gen. 49:18 enter this liturgy? It is not in the Talmud’s description of the prayers to recite upon retiring,[55] nor is it included in the prayer books of Amram Gaon or Saadia Gaon.[56] However, adjurations for help in understanding dreams that date before the ninth century give special attention to Gen. 49:18. For example, in a pre-bedtime Hekhalot[57] adjuration of the angel Ragshiel (רגשיאל) to provide clues that will render a dream intelligible, our verse appears once toward the beginning and later with seven permutations. The text of the adjuration, which evolved over the period between roughly 200 CE to 800 CE, includes many elements of what has become the traditional bedtime Shema.[58]

Likewise, the Havdalah of Rabbi Akiva, a magical/mystical text from the geonic period, which also includes portions of the Bedtime Prayer, calls for reciting this verse forwards and backwards.[59] Two other sources affirm the verse’s protective power at night. Shimmush Tehillim (שמוש תהלים), a popular medieval compilation on the magical uses of Psalms, refers to the verse in conjunction with recitation of Psalm 67 for protection at night from all enemies lurking about. It includes a short incantation to assure the safety of one’s family and property from thieves, which concludes with the verse.[60] In his book on gematria (גמטריא)[61], Eleazar ben Judah of Worms (c. 1176–1238) wrote that the verse should be said “on your bed in the name of Levakhi Ya’akat Shatvi [לוכי יעקת שתוי] and then Likhi V’akat Shatvi [ליכי ועקת שתוי].” These are six divine names, in two sets of three, each set composed of the Hebrew letters in the verse. As each name is said, Eleazar ben Judah recommends, keeping in mind (bekhavvanah [בכונה]) an additional set of divine names composed from the verse.[62]

By the medieval period, in some quarters, it had become customary to recite the verse as part of the bedtime liturgy. It appears in the instructions for these prayers found in Siddur Rashi, compiled in the 11th and 12th centuries,[63] and Eleazar ben Judah of Worms included it in his Bedtime Prayer liturgy. In Eleazar ben Judah’s terse list of elements for the liturgy, he merely lists the word, lishuatekha (לישועתך), toward the end of the liturgy, roughly where it appears now. But this very terseness suggests that readers would have been quite familiar with the reference.[64]

During this period, the custom of reciting permutations of the verse as part of the bedtime liturgy also took root. Rabbi Meir of Rothenberg (c. 1215–1293) prescribed facing six directions (the four points of the compass, plus up and down) and reciting a different permutation for the four directions of the compass, plus one for up and one for down.[65] (Conveniently, there are six possible permutations of this three word verse.) Matteh Mosheh (מטה משה) by Moshe ben Avraham of Przemyśl (c. 1550–1606), the Polish halakhist, explained that this would drive out demons.[66] Nathan of Hanover (d. 1683), who compiled a short collection of Isaac Luria’s liturgical practices, recommends three permutations of the verse but suggests that, while reciting it, one concentrate on the divine name it contains—the name that appears in Eleazar ben Judah’s amulet (figure 1) on the base of the Menorah Psalm (figure 2).[67]

THE AMIDAH[68]

Around the twelfth century, our verse found its way into the fifteenth benediction of Amidah, repeated three times daily except Shabbat and festivals.[69] The verse has been modified slightly:

את צמח דוד עבדך מהרה תצמיח, וקרנו תרום בישועתך, כי לישועתך קוינו כל היום. ברוך אתה יי, מצמיח קרן ישועה.

Cause the progeny of David, of Your servant David to blossom quickly. Let him shine in your deliverance, for we hope for Your deliverance all day long. Blessed are You, Adonai, who causes the light of salvation to blossom. [Emphasis added.][70]

Earlier versions of this benediction did not include the phrase in italics, and it still does not appear in the Yemenite prayer tradition.[71] The addition transformed part of Genesis 49:18 into the plural, and added the words “all day long.”[72] These last words come from Psalms 25:5, which are preceded by קִוִּיתִי (kivviti), the same word for hope that appears in Gen. 49:18. Although not a precise quotation of Gen. 49:18, scholars identify our verse as one of the sources of this addition to the Amidah.[73] It’s hard to know why this was added, but it seems to supply a justification for why God should hasten Israel’s messianic deliverance: because—despite temptations—Israel has not reneged on its hopes in God’s redeeming hand. The addition couches the prayer in implicitly covenantal terms. Israel has kept its part of the bargain by unwaveringly placing its hope in God who—someday—will bring messianic redemption. In any case, this addition to the Amidah pointedly identifies the Jewish People as those who have retained their hope for salvation, in contrast to those referred to in the Amidah’s twelfth blessing (which begins ולמלשינים אל תהי תקוה, “May there be no hope for slanderers…”) whose hope, according to the liturgy, will be taken away.

The kabbalist Isaac Luria (1534–1572, known as the ARI, flourished in Safed) began an interpretive tradition of this phrase in the Amidah that lives on and, in fact, has led to further modifications of the passage in various Sephardic traditions. Luria’s interpretation links the passage to a teaching in the Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 31a) that lists the six things a person will be asked about when he or she dies and faces judgment: Did you do business with integrity; did you establish fixed times for study; did you engage in procreation; did you hope for deliverance; did you engage in the dialectics of wisdom; and did you understand one thing from another (reason by inference)?[74]

According to Chayyim Vital (who was the key transmitter of Luria’s teachings), this passage in the Amidah refers:

…to what a person will be asked after his death. “Did you hope for deliverance?” Therefore, your intention when reciting this passage should be that you are among those who hope for deliverance from God.[75]

באמרן לישועתך קוינו כל היום יכוין למה ששואלין את האדם לאחר מיתתו. “צפית לישועה?” ולכן בברכה זו תכוין שאתה מן המקוים של הש”י.

Over time, Luria’s link between our passage in the Amidah and the Talmud’s story about judgment led others to make that connection explicit. Some claim that when Luria prayed and the prayer leader said “we hope for Your deliverance” (לישועתך קוינו, lishuatekha kivvinu), the congregation would respond with words that echoed those used in the Talmud: “and we hope for deliverance” (ומצפים לישועה) umtzappim lishu’ah.[76] Gradually, variations on these words found their way into the liturgy of some communities. For example, Chayyim Falagi (1788–1858), a Turkish scholar of Jewish law and kabbalah, used this wording: “we hope and we expect,” (קוינו וצפינו, kivvinu vetzippinu). He based this on a teaching from the Zohar (I: 4a), which, in turn, echoes the Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 31a. The Zohar alludes to God joining the Shekhinah and redeeming her from exile and says, “Whoever does not await [or hope, metzappeh {מצפה}] for this each day in that world has no portion here.”[77] “We hope and we expect” is now found in the nussach (נסח, ‘prayer rite’) of Sephardic “communities of the East,” (Edot HaMizrach, עדות המזרח, i.e., Jews with ancestry from Arabic-speaking lands).[78] The ‘Sephardic’ Hasidic nussach can be read as “we hoped for your deliverance… and we hope for deliverance” (קוינו… ומצפים, kivvinu … umtzappim).”[79] Whether or not this is its intention, this wording appears to draw a contrast between the past and present tense—i.e., “We hoped for salvation [then] and we hope for it [now].”

As noted, the Yemenite nussach of the Amidah does not include the phrase under discussion. Nonetheless, this community does maintain a custom based on the connection between Gen. 49:18 and the Talmud’s injunction to hope for salvation. For centuries, it has been customary for members of this community to begin their writings with the letters ,לק״י the first letters of the three words in Gen. 49:18. Joseph Kafach (1917–2000), long one of that community’s greatest scholars and religious leaders, links this custom directly to the desire to be counted among those who regularly fulfill the Talmud’s injunction about the significance of hope for salvation. Nowadays, religious web sites sponsored by Yemenite Jewish groups often write לק״י in the top right corner of the site.[80]

Regardless of which nussach one uses, this brief exploration sheds important light on a passage that we read three times daily, and to which may not have otherwise given much attention. Luria’s insight gives it a critical personal dimension. We are not just hoping for abstract messianic salvation but for personal salvation at the time of our death. Seen this way, the passage reminds us that our days are limited, and that our capacity to hope is critical to how we live and die, to how we judge ourselves and how we will be judged—by God, and by others.

ANI MA’AMIN: “I BELIEVE”[81]

For almost five hundred years there’s been a tradition for prayer books to include Ani Ma’amin (אני מאמין)—a short credo based on Maimonides’ ‘Thirteen Principles’—and to follow it with Gen. 49:18. The custom generally involves reciting three permutations of the verse in Hebrew and three in Aramaic, similar to what we’ve found in some amulets. Again, the definitive origins of the custom are difficult to pin down. The fact that the Thirteen Principles should have found their way into the siddur may be a reflection of what Maimonides himself wrote about them. After listing the principles in his commentary on the Mishnah (at the end of chapter 10 of Sanhedrin), Maimonides wrote:

לכן דע אותם והצלח בהם וחוזר(אלה) [עליהם] פעמים רבות והתבונן בהם התבוננות יפה ואם השיאך לבך ותחשב שהגיעו לך ענינו מפעם אחת או מעשרה הרי הש”י יודע שהשיאך על שקר ולכן לא תמהר בקריאתו כי אני לא חברתי כפי מה שנזדמן לי.

You must know them well. Repeat them frequently. Meditate on them carefully. If your mind seduces you into thinking that you comprehend them after one reading—or ten readings—God knows you are deceived! Do not read them hurriedly, for I did not just happen to write them down. ” [82]

A 15th century manuscript with a large collection of miscellaneous prayers includes a somewhat expanded version of Ani Ma’amin with a statement that takes Maimonides a step or two further:

וטוב לאומרן בכל יום אחר תפלתו כי כל שאומרן בכל יום אינו ניזוק כל אותו יום.

They should be recited daily after prayer, for whosoever recites them daily, will come to no harm all that day.[83]

When Ani Ma’amin made its first appearance in a siddur (published in Mantua, 1558) it was prefaced with a note in Yiddish observing that “Some have the custom to recite this also in the morning.” In this siddur, Ani Ma’amin is followed by the usual Hebrew and Aramaic permutations of Gen. 49:18.[84]

As to the connection between Ani Ma’amin and permutations of Gen. 49:18, several possibilities present themselves. First, if reciting the creed was believed to ensure a measure of protection, concluding it with an amuletic formulation of Gen. 49:18, a close relative of which had already begun to make liturgical inroads (e.g., the Bedtime Prayer and Wayfarers’ Prayer, below) makes sense. Second, in Sephardic communities where Ani Ma’amin was read in congregations (on a monthly basis), accounts suggest that the practice was emotionally very powerful. The creedal confession of faith was, after all, far more familiar to Christians than Jews. In that light, the amuletic conclusion is reminiscent of how the verse was used preceding the study of kabbalah, as a buffer between different states of consciousness. And third, the final element of Ani Ma’amin expresses belief in the resurrection of the dead. We’ve already encountered two connections between the themes of death and salvation and Gen. 49:18. The original locus of the verse is Jacob’s deathbed, and the Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 31a) lists hope in salvation as one of the criteria that will determine the outcome of Divine judgment upon death. The combination of all three factors may help explain the tradition of following Ani Ma’amin with permutations of Gen. 49:18.

Nonetheless, the juxtaposition of Maimonides, the arch rationalist, with the language of amulets, initially seems jarring. But when it came to permitting incantations over snake bites, or allowing women in childbirth to use amulets, Maimonides was lenient. He didn’t believe these practices contained any real power, but he understood that they might lift the patient’s spirits, not an outcome any good physician would ignore.[85] At the same time, it’s worth remembering that, despite Maimonides’ rationalism and general disdain for mysticism, kabbalists (e.g., Abraham Abulafia) and those inclined to the realms of quasi-magic, have had a long history of rooting their beliefs in his thought.[86]

THE WAYFARER’S PRAYER[87]

As does the Bedtime Prayer, the Wayfarer’s Prayer, Tefillat HaDerekh, includes multiple permutations of Gen. 49:18. How did the custom arise? The Babylonian Talmud (Berakhot 29b) contains the core of Tefillat HaDerekh, but does not include this or any other biblical verses. The verse does not appear in the siddurim of Amram Gaon or Saadia Gaon, or in medieval codes on the subject. Of note, however, the short discussion in the Talmud that precedes the prayer begins with an injunction attributed to Elijah, the archetypical wayfarer. Elijah says that before beginning a journey you must “beg leave of your Creator and set off.” The sense seems to be that travel, perhaps with interruptions of religious observance, implies distancing one’s self from God. Tefillat HaDerekh embodies a plea for Divine protection—interruptions of regular prayer notwithstanding—and blesses God as the One “who hears prayer.”

Let’s look at how Tefillat HaDerekh evolved over the centuries and at the role Gen. 49:18 came to play in it. In his Torah commentary on the verse, Rabbeinu Bachya ben Asher (רבינו בחיי בן אשר) (mid–13th century to 1340, Saragossa, Spain) wrote that “masters of the names” found a divine name in this verse that was useful against enemies [perhaps demons] when one was traveling.[88] He based this on his reading of a verse in the Samson story that says “he pulled with power,” vayyet bekho’ach, and brought the Philistines’ temple of Dagon down on his enemies (Judges 16:30). Bachya notes that the verse doesn’t say “with his power” but “with power,” which indicates “power from the Name. He combined power from the Name and his own power….”

לא אמר הכתוב: ויט בכחו, אלא “ויט בכח”, כלומר בכח השם, עם כחו, כי שתף כח השם עם כחו…

Bachya continues:

והשם היוצא מן הכתוב הזה הוא בסדר אותיות הכתוב והתיבות משולשות, וידוע ומפורסם הוא בנקודו, וצריך אדם להזכירו כסדרן למפרע ג”כ כדי שילך בדרך סלולה, וישיב אויביו אחור ומזה סמך לו אחור.

And the name that is derived from this verse is in the order of the letters of scripture with the words re-divided into triads, and with well-known re-vocalization. One must say it as rearranged so that one’s path will be smooth [as in Jeremiah 18:15] and he will turn back his enemies, which is why it is attached to the word “backward” [i.e., the last word at the end of Gen. 49:17].[89]

The divine name is none other than that which we previously encountered in Eleazar ben Judah of Worms’ amulet and the earliest known image of the Menorah Psalm found in illustrations 1 and 2.[90]

By the 16th century, customs associated with the Wayfarer’s Prayer had evolved considerably beyond the Talmud’s relatively terse blessing. Abraham ben Shabbetai Sheftel Horowitz (c. 1550–1615, Poland) began his discussion of the laws for travelers with a statement from the Talmud: “Whoever first prays and afterward departs on the road, the Holy one, Blessed be He, does his business for him” (Berakhot 14a).[91] “Therefore,” he wrote, “one should make it a habit before setting off on a journey to recite biblical verses requesting God’s mercy.” In his gloss on this work, Isaiah Horowitz (The Shelah, c. 1565–1630, Prague/Israel, the son of Abraham Horowitz) takes up the obligation of escorting travelers as they begin a journey. Isaiah Horowitz recommends that the traveler should say to the escort “peace be unto you” three times,[92] and immediately begin reciting verses requesting God’s mercy and Psalm 121. He concludes that it is “a universal custom” to recite Gen. 49:18 thirty times, and other verses six, ten, and five times.[93] According to some, it was also customary for the escorts to recite these some of these biblical verses, multiple times as well. As these customs continued to develop, they sometimes applied the practice of the thirtyfold repetition to three or six permutations of the Gen. 49:18—for a total of 90 or 180 repetitions![94]

Nowadays many prayer books have returned to more streamlined versions of the Wayfarer’s Prayer, closer to the Talmudic original, often without the biblical verses that had been added to the ritual over the centuries.[95]

BERIT MILAH: CIRCUMCISION[96]

Our last liturgical encounter with Gen. 49:18 brings us to the service for circumcision, and to various customs preceding the ritual itself. Here again the basic core of the liturgy derives from the Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 137b), but, over time, this core was embellished with allusions to biblical verses and personalities. At some point in the medieval period, Gen. 49:18 made its way into the evolving liturgy.[97] It does not appear in ceremonies included in the siddurim of Amram Gaon, Saadia Gaon, or in the medieval codes. In any case, the dangers and mystery associated with the birth process made it a critical occasion for the use of amulets to protect mother and child from demons, the likes of Lilith[98] and others. Boys needed special protection for eight days, and girls for twenty. Customs requiring the display of amulets on the four wall of an infant’s birthing room are described as far back as Sefer HaRazim, dating back to the Talmudic period, and these practices continue in some Jewish communities today.[99]

Here are two examples from several centuries ago. A complex amulet illustrated in Shorshei HaShemot, a compendium of divine names compiled in the 17th and 18th centuries, includes one element that protects newborn males from Lilith.[100] This part of the amulet includes the names of three angels the sight of which deprived Lilith of her power to harm a newborn male infant. Just below that appears a star of David surrounded by six abbreviated permutations of Gen. 49:18. An 18th century printed childbirth amulet with a text that was apparently common for this purpose—the museum that holds it has three different examples with the same text—includes a variety of biblical passages, including three abbreviated permutations of Gen. 49:18.[101]

Beyond surrounding the newborn with amulets, on the night before circumcision, an evening known as A Night of Watching or Guarding (Vachnacht [וואכנאכט], in Yiddish, Leil Shimmurim [ליל שמורים] in Hebrew), it was also customary to recite a special version of the bedtime Shema by the infant’s bedside. It included multiple repetitions of several biblical verses, and three permutations of Gen.49:18 recited a total of nine times.[102]

Just after the beginning of the circumcision ritual, when the mohel (מוהל, “circumciser”) identifies the chair of Elijah, he recites Gen. 49:18, followed by, שִֹבּרתי לישועתך יהוה, the first three words from a verse from Psalms, which, in English, are rather similar, “I hope, (sibarti) for your deliverance O Lord,” (Psalms 119:166).[103] The link between Elijah and Gen. 49:18 may have arisen because circumcision amulets frequently depict Elijah as protector of the child, and Gen 49:18 likewise often appears on childbirth amulets.[104] Bringing Elijah and Gen. 49:18 together at the berit was probably seen as a sure source of power to protect the helpless child at a point of extreme vulnerability to demons or simply to mishap as a result of the procedure—though the latter would most surely not have been understood that way. One commentary argues that we say the verses from Psalms and Genesis to make it crystal clear that we don’t expect salvation from Elijah, but only from God.[105] A more typical explanation for reciting these verses holds that, given the delicacy of the procedure that is about to unfold, these verses express our hope it will proceed without complication.[106]

There’s one more possibility. A midrash in Gen. Rabbah 99:11 links Elijah to the verse. Recall that Jacob proclaims his hope in God’s salvation between the words he speaks to Dan and Gad. The midrash recounts Jacob envisioning Samson’s death, and realizing that redemption wouldn’t come from Samson, a descendent of Dan, but from a descendent of Gad—whom the midrash identifies as Elijah.[107] The midrash seems to read Gen. 49:18 as pointing back to the failed redemptive efforts of Samson, and forward to a better outcome with the return of Elijah. With that in mind, pointing to Elijah’s chair and then reciting Gen. 49:18 makes sense since the midrash views this verse as alluding to Elijah’s messianic return.

SNEEZING

Our last encounter with Gen. 49:18 may occur frequently, but not as a part of the daily liturgy. At least since the 16th century, there have been those who have suggested reciting the verse after sneezing. Whether viewed as an omen for good or ill, sneezing has, of course, elicited a host of responses in all cultures since ancient times.[108] An early Jewish text, the Tosefta, a legal text from the third century, looked askance upon such practices. It opposed saying something as benign as “Healing,” merappei, when someone sneezed, and identified the practice with the abhorred, superstitious “ways of the Amorites.”[109] Suffice it to say, over time such stringencies faded.

The use of Gen. 49:18 as a response to one’s sneeze evolved from Midrashic ruminations about the connection between sneezing and death. The Babylonian Talmud (Sanhedrin 107b) reports that, until Jacob, there was no illness. So, Jacob prayed, and illness came into being. As it says, “Sometime afterward, Joseph was told ‘Your father is ill’” (Gen. 48:1). Pirkei de Rabbi Eliezer (chapter 52), a ninth century midrash, explains the Babylonian Talmud’s strange assertion that Jacob prayed for illness to enter the world. According to the midrash, because there was no illness until Jacob, death was preceded by a sneeze. With a sneeze, the soul departed through the nostrils.[110] Jacob prayed for illness so that he would be aware of death’s approach and would have time to convey his last testament to his family. God answered his prayer, as it is said, “Sometime afterward, Joseph was told ‘Your father is ill’” (Gen. 48:1). Therefore, concludes the midrash,

לפיכך חיב אדם לומר בעטישתו. חיים, שנהפך המות הזה לאור, שנאמר [איוב מא, י] “עטישתיו תהל אור.

“One is duty-bound to say to his fellow: Life! when the latter sneezes, for the death of the world was changed into light, as it is said, ‘His sneezings flash forth light’ (Job 41:10).”[111]

Yalkut Shimoni, a midrash from the 12th or 13th century, adds that, when one sneezes, one must praise God.[112]

By the 16th century, some highly regarded authorities asserted that, after a sneeze, it was obligatory to recite Gen. 49:18. (It’s worth noting that, during this period, it was also customary for Christians to reply to a sneeze with “Deus ti adiuvet,” “God help you.”[113]) Solomon Luria (c. 1510–1573, known as the Maharshal, Lithuania) outlined the following practice. Upon hearing one’s fellow sneeze one should say, Asuta (אסותא, literally “cure” or “remedy” in Aramaic). The one who sneezed first should say, “Baruch tihyeh” (ברוך תהיה, “Blessed are you!”( and then should recite Gen. 49:18.[114] Luria bases the custom of saying asuta on the fact that, when Abraham prayed for the recovery of the women in Avimelech’s household (Gen. 20:17), soon thereafter Sarah became pregnant. Similarly, after Job prayed for his friends, God restored Job’s own fortunes. One who wishes healing to someone who sneezes may likewise receive a benefit. But Luria didn’t explain why one who sneezes recites Gen. 48:18. Isaiah Horowitz (1565–1630) supplies the explanation. He concludes a discussion about the importance of praising God for everything an individual experiences—good, as well as bad—with a comment about sneezing. He recounts the story from Pirkei de Rabbi Eliezer and says that he’d heard about the custom of reciting Gen. 49:18. “It’s nice,” he says, “and the intention behind it is to praise God. Just as You saved me now (from death through a sneeze), so I hope for Your [ultimate] salvation [in the future].”[115] Nowadays, this custom is not widely practiced, although codes as authoritative as the Kitzur Shulchan Arukh of Shlomo Ganzfried (1804–1886), and the 1906 Mishnah Berurah by Yisrael Meir Kagan, support it, as does Ovadia Yosef, the former Chief Rabbi of Israel.[116]

CONCLUSIONS

As we’ve seen, the earliest appearances of permutations of Gen. 49:18 are found in adjurations from the Hekhalot literature reflecting mystical practices from the early rabbinic through the Geonic periods. The adjurations concern the wish to understand dreams, and they contain passages that are similar to what evolved into the Bedtime Prayer. These texts made their way to Europe via Italy, where they were absorbed by members of the Kalonymos family, who moved to the Rhineland in the early medieval period and founded the Chasidei Ashkenaz movement, which would influence Jewish religious practice in Germany for centuries to come.

Deeply steeped in magic and mysticism, Eleazar ben Judah of Worms and Meir of Rothenberg—two leaders of that movement—recommended concentrating on, or reciting permutations of, the verse to ward of demons during the night. Scholem credits the Chasidei Ashkenaz with developing what he called “the mysticism of prayer” “or the magic of prayer,” “a renewed consciousness of the magic power inherent in words” and the discovery of “multitude of esoteric meanings in a strictly limited number of fixed expressions.”[117] The community also employed adjurations to answer “dream questions.” In an amulet for protection against an enemy’s weapons, Eleazar ben Judah included a divine name based on the verse. That same divine name appeared in the earliest known version of the Menorah Psalm in the 14th century, which, during that period, was said to have been inscribed on the shield of David. In Spain, Bachya ben Asher (d. 1340), whose popular commentary on the Torah drew heavily on mysticism, noted that this divine name was well known, and that reciting it would assure one of a safe journey. By the end of the medieval period, Gen. 49:18 was well on the way to becoming entrenched in practices to provide safety from demons in the night and enemies on the road.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, influential rabbis inclined to mysticism—Isaiah Horowitz and Solomon Luria among them—spread these traditions. Solomon Luria’s work helped establish two customs involving the verse: decorating the door of the holy ark with the Menorah Psalm with Gen. 49:18 at its base; and reciting the verse upon sneezing. This period also saw the entry of Ani Ma’amin into the prayer book, followed by permutations of the verse in Hebrew and Aramaic.

The sources and customs surrounding the verse have given rise to, essentially, three interrelated ways of using the verse: 1) as it appears in the Bible or with slight variation; 2) with permutations; and 3) as a source of divine names. In the first case, when the verse is recited in its relatively unmodified form (as in the Amidah, the circumcision liturgy, or after sneezing), it echoes Jacob’s hope for salvation, and fulfills the Talmudic injunction that upon death favorable judgment will depend on whether or not during life one hoped for salvation.

In the second instance, when recited with permutations (in the Bedtime and Wayfarer’s Prayers, and following Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles), it harkens back to amuletic sources. In addition to its inherent power as Jacob’s parting words to God, those inclined to magic may have been drawn to the fact that, among the special club of three-word biblical verses, this is the only one that retains its precise meaning regardless of the order of its words. In accordance with the principles of sympathetic magic, it is as if this verse’s imperviousness to disturbance embodies the capacity to overcome outside forces, come what may. This alone would have endeared the verse to practitioners of magic. From a mystical perspective, these permutations may also have embodied a solution to what Moshe Idel called “one of the most important problems in Kabbalist theosophic thought: how to explain the absolute unity of the divine powers.” Idel suggests that, at least for some kabbalists, the solution was “unity within multiplicity,” a solution that he suggests was embodied by the form of the menorah—a unified symbol with distinct elements.[118] The same approach may help explain the fascination with permutations of Gen. 49:18. The verse’s underlying unity of meaning remains despite the multiplicity of permutations.

Finally, we’ve seen that the verse also came to be understood as a source of numerous divine names, one of which includes repetitions of many different triads of the verse’s letters—as in the ritual preceding the study of kabbalah—and functions not just as a means of affording protection but as a means of embodying, and possibly inducing, an altered state of consciousness. The divine name in the base of the Menorah Psalm simply keeps the order of the verse’s letters but regroups them. On one level this reflects the mystical conviction expressed by Nachmanides (1195–1270, Spain) that “the whole Torah is comprised of Names of the Holy One.”[119] In that sense, this verse is no different than any other. But perhaps the divine names associated with this verse do enjoy a certain pride of place through the frequency of their appearance—from early notions of its presence on David’s shield that developed in medieval Europe, to Persian amulets from the 19th century. To the extent that that is true, it no doubt reflects the potency not just of these names, but of the previous two factors as well: the original context of the biblical verse and its uncanny ability to retain its meaning even when the order of its words is turned every which way. By the medieval period, these three factors had sufficiently coalesced to give the verse a special appeal, one that only grew with the passage of time, allowing it to become the “go-to” verse for a variety of situations.

What characterizes these situations? If we look at the cases where the verse appears in the liturgy—the Amidah’s prayer for messianic salvation, the coda to Maimonides’ Thirteen Articles of Faith, the Bedtime Prayer, the Wayfarer’s Prayer, the liturgy for circumcision, and the reply to sneezing—it becomes clear that they all lie at a threshold, a transition from one state or place to another. Remember the verse’s original context, Jacob’s brief address to God, his last, sandwiched between the testament he delivers to his children as death approaches—a verse that is “betwixt and between” if there ever were one.[120] The fact that most traditional commentators viewed the verse as a vision of the tribe of Dan’s future, a border tribe that never managed to firmly root itself in its ancestral territory, further augments its transitional context. Gen. 49:18 appears in ritual frameworks surrounding what Arnold van Gennep classically defined as rites of passage, in this case what he called “liminal (or threshold) rites.”[121] Gennep differentiated between direct and indirect rites, the latter involving the kinds of practices with which Gen. 49:18 is generally associated:

A direct rite, for example a curse or a spell, is designed to produce results immediately, without intervention by any outside agent. On the other hand, an indirect rite—be it vow, prayer, or religious service—is a kind of initial blow which sets into motion some autonomous or personified power, such as a demon, a group of jinn, or a deity, who intervenes on behalf of the performer of the rite. The effect of a direct rite is automatic; that of an indirect rite comes as a repercussion.[122]

Gennep concludes his discussion of rites of passage with the observation that:

[t]he idea in question becomes simple and normal if one accepts the following view: the transition from one state to another is a serious step which could not be accomplished without special precautions.[123]

The uses of Gen. 49:18 are a remnant of an era when life overflowed with such precautions. Malinowski’s understanding of magic is particularly apt to the career of this verse:

The function of magic is to ritualize man’s optimism, to enhance his faith in the victory of hope over fear. Magic expresses the greater value for man of confidence over doubt, of steadfastness over vacillation, of optimism over pessimism.[124]

Aside from embodying access to the powers that afford protection at these moments of vulnerability—God or God’s names or divine agents—the verse also recommends the stance we ought to take in facing these transitions. We should face them with hope—the conviction that we can muster the means to traverse these thresholds and that we are not alone in that endeavor. C. R. Snyder (1944-2006), one of the most important researchers on hope, wrote a book called the The Psychology of Hope. In explaining the subtitle of that book he wrote:

I believe that life is made up of thousands and thousands of instances in which we think about navigating from Point A to Point B. . . . It is the reason that this book is subtitled You Can Get There from Here.[125]

As Snyder explains, hope is the conviction that we can find the will and the way to make it from here to there. Those who prescribed reciting Jacob’s deathbed expression of hope for God’s salvation—in all its permutations and on so many occasions of danger and transition—shared the same conviction.

Whoever penned Gen. 49:18 would doubtless be surprised at the life it has acquired in Jewish practice over the millennia. “Turn it and turn it, for everything is in it,” said Ben Bagbag about the Torah.[126] He could certainly have said the same of this verse alone.

David Arnow is the author of Creating Lively Passover Seders: A Sourcebook of Engaging Texts, Tales and Activities (Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights, 2011 [2nd edition]), co-editor with Lawrence A. Hoffman of My People’s Passover Haggadah (Jewish Lights, 2008 [two volumes]) and co-author with Paul Ohana of Leadership in the Bible: A Practical Guide for Today (Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2014). A psychologist, he is the author of numerous articles on the Passover Haggadah and other subjects of Jewish interest

-

* Many people helped me in my research for this article. Thanks to Jeffrey Hoffman, Noah Arnow, Elie Kaunfer, Alan Cooper, Jay Rovner, Jerry Schwarsbard, Daniel Abrams, Alexander Gordin, Marc B. Shapiro, Jeremy Meyerowitz, Uri Ehrlich, Ronald Hendel, Matthew Goldstone, Jonathan Jacoby, and John L. Rosove. Special thanks to Richard Claman for his careful editing and many helpful suggestions. ↑

-

Unless otherwise noted, biblical translations follow the New Jewish Publication Society Hebrew-English Tanakh (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1999). Other translations, if not otherwise noted, are mine. In terms of this particular verse, most translations render “wait” instead of “hope.” E. A. Speiser’s The Anchor Bible: Genesis (New York: Doubleday, 1964, p. 362) offers this: “I long for your deliverance, O Yahweh.” Everett Fox’s The Five Books of Moses goes with “wait-in-hope” (New York: Schocken, 1995, p. 232). In a personal communication (April 6, 2020), Ronald Hendel, author of a forthcoming Anchor Bible volume on Genesis, says, “Either ‘wait’ or ‘hope’ would be correct. The verb in Hebrew can mean both.” Philip Birnbaum’s The Daily Prayer Book (New York: Hebrew Publishing Company, 1992, p. 2) renders: “For thy salvation I hope, O Lord.” Jacob Neusner uses a similar translation in his many books. See, for example, his Judaism & Christianity in the Age of Constantine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), p. 57. Johannes Botterweck et al. would seem to support this translation. In an extensive discussion of this verb, they conclude that it connotes ‘hope’ when YHWH is “directly or indirectly the object of the verb” or “named indirectly or by extension” in passages speaking of God’s name or help, as in this case (pp. 568-69). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren, Heinz-Josef Fabry (Grand Rapids, MI: William. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003), vol. 12, pp. 564-573. The probable late dating of the verse also justifies this translation [see note 11], because other translators regularly translate the identical form of the verb in this verse as ‘hope’ when it appears in the Psalms or Job. See, for example, the translations of Psalms 25:5, 40:2, 130:5 and Job 30:26 in Robert Alter’s The Hebrew Bible (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018). These considerations lead me to have chosen the translation above. ↑

-

Siddur Sim Shalom for Weekdays (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly and the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, 2003), p. 169. ↑

-

See, for example, the Shabbat and Holiday Siddur published by Temple Israel of Hollywood (7300 Hollywood Blvd, Los Angeles, CA, 2006), p. 257. ↑

-

Birnbaum, supra fn. 1: following the Thirteen Principles, see p. 155 and following the Bedtime Prayer, see p. 783. ↑

-

See, for example, The Artscroll Siddur: The Rabbinical Council of America Edition, Ashkenazic version (New York: Mesorah Publications, 1990), p. 222 ↑

-

Biblical verses are occasionally repeated in liturgy, and there is one case in which we repeat a verse backwards—Exodus 15:16, in the Blessing for the New Moon. ↑

-

Birnbaum, p. 2. ↑

-

Genesis 49:16–18. Except for the last line, the translation follows the New Jewish Publication Society Hebrew-English Tanakh (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1999). ↑

-

Raymond De Hoop, Genesis 49 in Its Literary and Historical Context (Brill: Leiden, 1999), p. 557. See also Studies in Ancient Yahwistic Poetry by Frank Moore Cross and David Noel Freedman (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1997 [first published in 1975]), p. 60, note 65. ↑

-

Nahum Sarna, The JPS Commentary on Genesis (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), p. 341. It should be noted, however, that Sarna does not treat our verse as an interpolation, but rather follows the traditional approach of trying to link it to the “blessing” of Dan. ↑

-

Quoting the Jerusalem Talmud, Rashi (1040-1105, France) explains this because the tribe had a large population. The same source asserts that the Danites would find and return to the Israelites any objects that had been lost on the journey. In any case, Dan’s position as a buffer between the Israelites and potential attackers placed this tribe in a more precarious position than others. ↑

-

Nahum Sarna, The JPS Commentary on Genesis (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), pp. 340. For more on the curious history of the Tribe of Dan see “And Dan, Why Did He Remain In His Ships,” by Yigal Yadin, The Australian Journal of Biblical Archeology, vol. 1, no. 1, 1968, pp. 9-23, accessed May 26, 2020 and “Tribe of Dan: Sons of Israel or of Greek Mercenaries Hired by Egypt?” by Philippe Bohstrom, Haaretz, Dec. 4, 2016, accessed on May 26, 2020. ↑

-

Aside from Christian sources that use these passages from Genesis and Jeremiah to “prove” that the anti-Christ will come from the tribe of Dan, I am unaware of any traditional commentators that note the connections between the passages. Mark W. Bartusch is the only Bible scholar I’ve found who noted a relationship between our passages. Bartusch only focused on one of the shared words (נחש, serpent), and the similar sounding names of the specific serpents in Gen. 49:17 ((שפיפון and Jer. 8:17.(צפענים) Perhaps that is why he concluded that “The full significance and meaning of this possible connection between these two texts cannot be determined at the present time.” See Mark W. Bartusch, Understanding Dan: An Exegetical Study of a Biblical City, Tribe and Ancestor (London: Sheffield Academic Press, 2003), p. 226. The notion that Gen. 49:18 would seek to cast Dan in a favorable light, accords with the findings of Jean-Daniel Macchi who argues that Gen. 49:13-21 derived from a North Israelite source. See Macchi’s Israël et Ses Tribus Selon Genèse 49 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1999. Macchi does not mention the Gen. 49/Jer.8 connection, but in a personal communication (June 3, 2020), he expressed agreement with my observations. One additional connection between Gen. 49:18 and the tribe of Dan may be worth noting. According to the book of Judges (18:7, 14, 27, and 29), the tribe of Dan settled in a city called Laish (ליש). These are the first three letters of the first word in Gen: 49:18, לישועתך! ↑

-

For a good overview of commentaries on this verse, see Nechama Leibowitz, New Studies in Bereshit/Genesis (Jerusalem: World Zionist Organization, undated), fourth edition, pp. 548–555. ↑

-

Moses Alshekh, Torat Moshe, משה אלשיך, תורת משהBereshit, Vayechi, 1595? Belvedere, p. 81a. Hebrew Books 45292. Alshekh’s reading also finds support in the Zohar. See fn. 11 re Zohar 1:244b. ↑

-

Exodus Rabbah 30:24, translation adapted from the Soncino Midrash Rabbah 3rd Edition (London: Soncino Press, 1983), p. 375. Midrash is a genre of rabbinic literature which uses a variety of techniques to draw out meaning from biblical texts. ↑

-

Given the attraction the verse has held for mystics, it is curious that the verse rarely appears in the Zohar. It is only discussed on 1:244b. The Zohar associates the verse with the story of Samson, and alludes to the notion that “’your deliverance’ refers not only to human deliverance (of Dan, the nation, and Jacob) but also of the deliverance of Tif’eret, known as YHWH” (The Zohar: Pritzker Edition, translation and commentary by Daniel C. Matt (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006), vol. 3, pp. 495–496. ↑

-

For introductions see, Gideon Bohak, Ancient Jewish Magic (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008) and Joshua Trachtenberg, Jewish Magic and Superstition: A Study in Folk Religion (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004, [originally published in 1939]). ↑

-

Geoffrey W. Dennis. The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism (Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2016, 2nd Edition), p. 61. See also entries for “Theurgy” and for “Magic.” It is worth noting that two of these verses, Gen. 49:18 and Num. 6:24, contain just three words, and as such belong to a group of fourteen such verses in the Torah. These verses were long thought to have protective value, and as a result were recited at different times. The custom reaches back at least to the Havdalah of Rabbi Akiva. See Gershom Scholem “Havdalah d’Rabbi Akiva,” Tarbiz, vol. 50, pp. 243–281, .(הבדלה דר’ עקיבא ,תרביץ) This is a mystical/magical text from the geonic period. A list of three-word biblical verses therein concludes with Gen. 49:18, repeated forwards and backwards (p. 269). This is the only verse in the list treated this way. There is a long history of reciting these verses just after the conclusion of the Sabbath. See for example, Matteh Yehudah, by Jacob ben Raphael, יעקב בן רפאל, (Petrakov, 1905), p. 121. (Available on Google Books underמטה יהודה .) See also Siddur Otzar HaTefillot, nusach Sepharad, (סדור אוצר התפלות, נוסח ספרד), Vilna, 1928, p. 434a and b. For a contemporary example see, Verses of Blessing for Motzai Shabbat, (accessed April 7, 2020). For a good overview of the use of biblical verses in magical texts see, Joseph Angel, “The Use of the Hebrew Bible in Early Jewish Magic,” Religion Compass, 3/5 (2009), pp. 785–798, (accessed April 7, 2020). ↑

-

For additional examples of amulets containing Gen. 49:18, see Isaiah Shachar, Jewish Tradition in Art: The Feuchtwanger Collection of Judaica (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1981), catalogue numbers 782, 784, 237, 804, 833, and 839. See also Joseph Naveh and Shaul Shaked, Magic Spells and Formulae: Aramaic Incantation of Late Antiquity (Jerusalem: Magnes Press), 1993, p. 240. Gen. 49:18 also appears in the text of a lengthy amulet discovered in the Cairo Geniza that seeks to protect a man’s wife from slander and witchcraft and to restore her love of him. It begins, “[In the] name of the Lord, may we do and succeed.” Then come three permutations of Gen. 49:18. Lawrence H. Schiffman and Michael D. Swartz, Hebrew and Aramaic Incantation Texts from the Cairo Genizah (Sheffield, Sheffield Academic Press, 1992), pp. 64–68. These authors (at p. 154) report that the Oxford 1539 manuscript of this text includes three permutations of Gen. 49:18 and six of II Samuel 5:16=I Chronicles 3:8. ↑

-

Gershom Scholem, “The Star of David: History of a Symbol” in Scholem’s The Messianic Idea in Judaism (New York: Schocken Books, 1971), pp. 257–281. ↑

-

Talmudic and mystical discussion of what are deemed to constitute of divine names extend far beyond the familiar names of God found in the Bible. In the mystical tradition, knowledge of divine names provided access to divine power. Lengthy catalogues of divine names were compiled, detailing the powers of specific names as well as when and how to invoke them for maximal benefit. Often divine names are written out in triads of Hebrew letters, as is the case in Figure 1. ↑

-

This amulet appears in Sefer Raziel HaMalakh, p. 44b, which was first published in 1701 in Amsterdam. For the attribution to Eleazar ben Judah see Encyclopaedia Judaica, “Raziel, Book of.” ↑

-

Sefer Raziel Ha Malakh (accessed April 13, 2020) ↑

-

Shorshei HaShemot (Jerusalem: Hotsaʾat Nezer Sheraga, 1999), vol. 1 p. 371, no. 1. The compendium is based on Shorshei HaShemot by Moses ben Mordecai Zacuto (משה זוכתא בן (מרדכי (c. 1620–1697), expanded by Abraham Alnakar (אברהם אלנקאר) (1740?–1803) and published as Shorshei HaShemot. ↑

-

For an excellent study with plenty of illustrations, see Esther Yuhasz, “Bein ruach l’chomer, bein tekst l’tmunah: l’sh’eilat hitzvarutav shel chefetz dati askanceb’heksher h’yihudi—ha mikre shel ha ‘shiviti-menorah,” Mechkerei Yerushaliym BeFolklor Yehudi, 24–25 (2006–2007), pp. 350–381. (אסתר יוחס, בין רוח לחומר, בין טקסט לתמונה: לשאלת היווצרותי של חפץ דתי בהקשר היודי – המקרה של ה”שויתי- מנורה,” מחקרי ירושלים בפוקלור יהודי.) Also see various articles in In the Light of the Menorah: The History of a Symbol (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum and the Jewish Publications Society, 1999). See, especially, “The Amuletic Menorah” by Eshter Yuhasz in ibid. For a good treatment of the mystical aspects of the Menorah Psalm, which includes a few paragraphs about Gen 49:18, see Bedrich Nosek, “Synagogical Tablets from the Collections of the State Jewish Museum [of Prague],” Judaica Bohemiae 18:2 (1982), pp. 93-94. ↑

-

Sefer Abudarham, (Kontashtina, 1513), p.3 3b right column. ↑

-

For the complete text and illustration, see “A Further Thirty-three Highly important Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts” (Zurich: Parke Bernet, 1978), p. 109 or Eshter Yuhasz, “Bein ruach l’chomer….” Illustrations 12a and 12b, supra, fn. 26. ↑

-

It must be said, however, that others used this same divine name in very different contexts. For example, Chayyim Vital (חיים ויטאל) (1542-1620, the foremost disciple of the mysitic Isaac Luria in Safed states that the following unification formula (i.e., yichud [יחוד]) should be recited before studying halakhah: “May it be Your Will, Adonai, our ליש ועת ךקו יתי יהוה In the name of God and God of our ancestors, that you will open my heart to this halakhah to understand it precisely and to understand all the different opinions about it.” (Chayyim Vital, Peri Etz Chayyim, (Dubrovno, 1804) Sha’ar Hahagot HaLimmud חיימ שער ההגות הלמוד] [פרי עץ chapter 11, p. 80a (accessed November 25, 2019.) ↑

-

The spelling of Gen. 49:18 in the oldest examples of the Menorah Psalm differs from later instances. The earliest cases read כקו compared to ךקו in later versions. The former changes the final form of the letter khaf (כ) into a regular khaf, while the latter preserves the final form of the letter (ך) at the beginning of a word. I have found nothing to explain this difference, but it is worth noting for the following reason. Eleazar ben Judah’s amulet illustrated above is the oldest source I have found using this divine name and it uses כקו. Joseph Dan speculated about a relationship between the earliest writings about the Menorah Psalm and the Chasidei Ashkenaz community of the 13th century. (See Yuhasz’ “The Amuletic Menorah,” note 11 in In the Light of the Menorah, supra, fn. 26.) Eleazar ben Judah was a central figure in this community, and it is of some interest that his spelling of the divine name in his amulet is the same as that found in the earliest illustrations of the Menorah Psalm, which date from about a century after his death. ↑

-

For a good quality reproduction of the illustration in Luria’s book, see Ilia Rodov’s The Torah Ark in Renaissance Poland (Leiden: Brill, 2013, pp. 183–203 and fig. 96. For the Ark of the Cracow Synagogue see, Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 5, p. 1035. ↑

-

Solomon Luria (Ma’harshal) Menorat Zahav (שלמה בן יחיאל לוריא , מנורת זהב) , Prague, 1669, p. 5 (second to the last paragraph), (accessed on November 10, 2019.) ↑

-

In Kaballah, sefirot are the emanations through which God created and sustains creation. ↑

-

See Lihi Habas, “Identity and Hope: The Menorah in the Jewish Catacombs of Rome,” in In the Light of the Menorah, supra, fn. 26, pp. 76-80. ↑

-

For illustrations see Esther Yuhasz, “Bein ruach l’chomer…” illustration 20, and Yuhasz in In the Light of the Menorah, p. 67. Note that in versions of the Menorah Psalm which include the words from Psalms 16:18, Shiviti Adonai l’negdi tamid, Gen. 49:18 does not always appear. ↑

-

T. Schrire, Hebrew Amulets: Their Decipherment and Interpretation (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966), pp. 50–51, and plates 12, 14, 37, 39, and 50. Schrire’s study also includes a Hebrew-Christian amulet that lists three forms of Jesus’ name in Hebrew: Yeshu (ישו); Yehoshua (יהושע); and Yeshuah (ישועה). The amulet includes the head of Christ surrounded by these names, all of which include variants of the word for ‘salvation’ that appears in Gen 49:18. See p. 71 and plates 42 and 43. ↑

-

See Schrire pp. 127–130. ↑

-